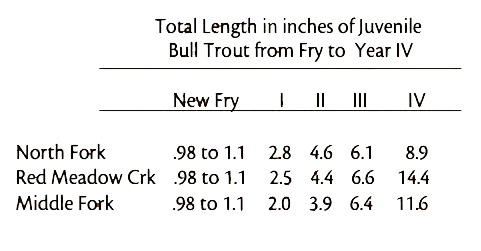

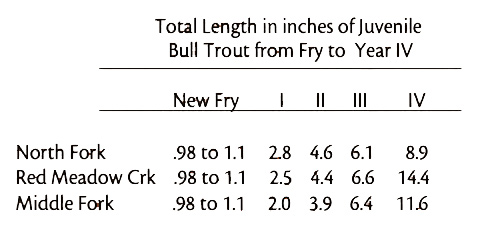

Juvenile bull trout forage near the bottom and in the middle of the water column, but they do not feed at the surface. They are opportunistic feeders, meaning they will eat whatever is available in the way of insects, snails, leeches, fish eggs, and fish that they can fit in their mouths. They are vorcious feeders because they are growing at a rapid rate.

When they are young and small, bull trout eat primary aquatic insects, especially the larvae of mayflies and aquatic flies. But as they grow, they shift their diet. When they get to be a little over four inches long, they start feeding on small fish (sculpins, mountain whitefish and trout fry), and soon their diet is primarily fish. It is a permanent shift; subadult and adult bull trout are considered piscivores (fish eaters). Like adults, juveniles can be aggressive feeders. In one study, the stomach of a 3.5-inch-long juvenile bull trout was found to contain a 1.8-inch-long rainbow trout.