History

The History of Fire and the Human Use of Fire in the Northern Rockies

History

The History of Fire and the Human Use of Fire in the Northern Rockies

History

The History of Fire in the Northern Rockies

Along with the Great Fires of 1910, the opening of the Flathead Reservation to non-Indian settlement led to the near total elimination of tribal traditions of burning the land. It also helped usher in a non-Indian approach to forestry.

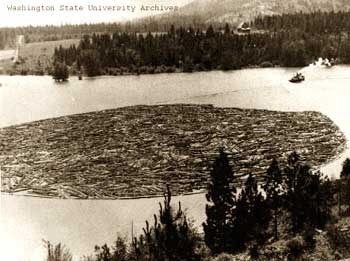

The Photos Below

With the exception of the first photo, Logs on Lake Pend Oreille, all of the photographs in this series are from: "Report on Logged-Over Ponderosa Pine Lands on the Flathead Indian Reservation, Montana", by Harold Weaver. At the time of the report (1937), it had long been "a matter of common knowledge that large areas of what was originally excellent forest lands on the Flathead Reservation had been denuded" of all trees by aggressive logging and subsequent fires that consumed any regeneration. The report was done to document the need for replanting. Use the navigation bubbles at the bottom of the photo to move through the photos.

The opening of the reservation to non-Indian settlement was accomplished through the Flathead Allotment Act, a legislative spin-off of the General Allotment Act or Dawes Severalty Act passed by Congress in 1887. The Dawes Act set up the basic policy of allotment—a scheme that broke up communally-held tribal lands into tracts assigned to individual Indians, and then declared any remaining lands within the reservation to be “surplus” and threw them open to non-Indian homesteaders. Because each reservation was established by a specific treaty with specific language regarding lands and tribal sovereignty, Congress had to pass separate bills applying the General Allotment Act to the various reservations in the years after 1887.

Sam Resurrection, who along with other tribal leaders fought the Flathead Allotment Act and opening of the Reservation to white settlement as a violation of the Hellgate Treaty. Photo circa 1915. Photo courtesy of Salish Pend d'Oreille Culture Committee.

For Indian people, allotment was perhaps the single most devastating piece of legislation in U.S. history. In 1887, American Indian people controlled a total of some 138 million acres; by 1934, when FDR’s Indian Reorganization Act finally put an end to the policy, their lands had been reduced to 48 million acres—a loss of 90 million acres, two-thirds of the native landbase in 1887—a landbase that was already radically reduced from its original extent. The Allotment Act continues to play a powerful role today in the socioeconomic depression and cultural loss besetting many tribes across the country.

On the Flathead Reservation, the effects of allotment were as dramatic and as damaging as anywhere in the nation. Between 1910 and 1929, 409,710 acres of the reservation’s best agricultural lands were made available to homesteaders. Between 1910 and 1935, another 131,239 acres of original Indian allotments were transferred into fee patent status, with nearly all eventually sold to non-Indians. Many of the sales were forced upon Indians by federal agents helping storeowners and others cash in small debts. Tens of thousands of additional acres were seized by the government to build townsites, create “villa sites” on Flathead Lake for generally wealthy vacation-home builders, establish a 16,000-acre National Bison Range, support public schools, build roads, construct dams and canals for irrigation, establish research stations for the University of Montana, and other purposes. Federal maps for a while referred to the area as the “former Flathead Indian Reservation.”

Joseph Dixon (R-MT), author of the Flathead Allotment Act. Photo circa 1905.

Until 1910, the Flathead Reservation was still a largely native world, with few non- Indians, few fences, and fewer roads. The only businesses legally operating within the reservation were licensed Indian traders, and many of them were forced to learn at least one of the native languages in order to operate successfully. All that changed overnight. From 1910 on, the best land and the economy as a whole were firmly controlled by non- Indians. Now it was Indian people who had to learn English in order to make a living. The opening of the reservation to white settlement had accomplished in a few months the kind of cultural change that Jesuit boarding schools could not effect in 30 years. Gradually increasing numbers of Indian parents stopped teaching their children how to speak Salish and Kootenai, because they felt that in this new world, traditional linguistic and cultural knowledge would be more of an impediment than an asset.

The further marginalization of tribal ways of life meant the near elimination of the traditional use of fire. As we have seen, federal Indian policies in the late nineteenth century had already made it difficult for tribal people to burn, even within the bounds of the reservation. Now it was nearly impossible, with the majority of the reservation’s population comprised of non-Indians, their newly established towns and ranches sprinkled across the Mission and Jocko valleys. Tribal people could continue to use tribal lands for hunting, fishing, and gathering roots, berries, and medicines. But burning became a much more difficult—much riskier—proposition.

The rising economic and political power of non-Indians on the reservation was aided by the lack of any effective countervailing tribal governmental structure. For years, the traditional chiefs had been undermined by U.S. agents and superintendents. After the opening of the reservation, Superintendent Frederick Morgan established a Flathead Business Committee, consisting mainly of mixed bloods and whites married to tribal members. They served as little more than a rubber stamp for BIA policies. Over the next two decades, various groups arose, each claiming to be the legitimate government of the tribe. All sought the approval of the traditional "full bloods," and on numerous occasions, the traditional leaders were manipulated into signing documents they didn't understand.

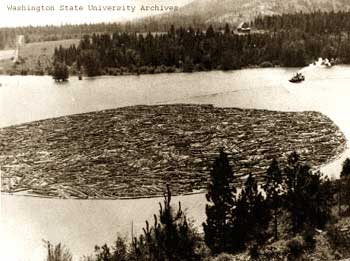

Polley Lumber Company loading logs on a train, circa 1930. Photo by R.J. McKay Collection, K Ross Toole Archives, Mansfield Library, U of M.

Beginning in the 1880’s, the Northern Pacific Railroad had logged extensively within its 56-mile-long, 200-foot right-of-way in the southern portion of the reservation, and apparently also committed numerous acts of timber trespass on adjoining tribal lands. But other than the NPRR logging, the federal government allowed no commercial or large-scale timber harvests within the reservation prior to 1900.

Between the turn of the century and 1910, the government did approve a few salvage sales, some of considerable size. In 1907-09, nearly twenty million board feet of “dead and downed” timber were logged under special authorization from the Office of Indian Affairs – over eight million board feet in the Post Creek district by the John O’Brien Lumber Company of Somers and over nine million board feet in the Evaro-Jocko district by Edward Donlan and W.B. Russell of Missoula.iii Soon after, in the wake of the 1910 fires, the government sold about three million board feet of burned timber, mostly in the Rocky Point area on the west shore of Flathead Lake, to the Cramer Lumber Company.iv Even those sales, however, were minuscule compared to what would follow in the next two decades, particularly in the southern end of the reservation, home to the most massive old growth ponderosa pines—the product of centuries of systematic traditional fire management using frequent low-intensity burns.

In 1917, two enormous sales were executed in the southern end of the reservation. The Polley Lumber Company logged over 46 million board feet in the Schley and Arlee areas. And the Heron Lumber Company, headed by Edward Donlan, clearcut almost 62 million board feet of mature pure ponderosa stands in the Evaro area. In 1923, Heron Lumber would cut an even bigger swath in the Valley Creek area, harvesting a staggering 146 million board feet. Tribal elder Harriet Whitworth, who was born in 1918 and grew up in Valley Creek, remembers the heartbroken feeling among many Salish people as the great trees were knocked down and hauled out. The creek itself, a teeming trout fishery, completely dried up for a period of time after the trees were removed.v

On the reservation as elsewhere in western Montana, this industrial scale of exploitation of natural resources was directly connected to the development of critical infrastructure—and in particular, railroads. Railroads enabled the conversion of raw natural materials—logs, copper, wheat, livestock -- into marketable commodities, linked by the steel roads to regional, national, and international markets. The logging of Evaro, Arlee, and Valley Creek was made possible by the proximity of those units to the mainline of the Northern Pacific Railroad.

The reach of the railroad on the Flathead Reservation was extended further in 1916, when the Northern Pacific secured from the government approval—and right-of-way—to build a spur line from Dixon north to Polson, thus bringing the Mission Valley into the orbit of the markets. In 1917, the railroad was built, and that same year, the Polley Lumber Company began intensive harvesting of the gigantic ponderosas near Ronan, at the western base of the Mission Mountains.vi Between the forests and the Dixon-Polson line, Polley built small-gauge railroads to haul the out trees, many of which were so enormous that just one log took up an entire rail car. Between 1917 and 1928, Polley cut 108 million board feet in the area.vii

Each of these areas—Evaro, Arlee, Schley, Valley Creek, and also further north in the Ronan area of the Mission Valley—is an ancient traditional center of population for Pend d’Oreille (and in more recent years, Salish) people. Evaro is called Snɫl̓ʔoy̓čô, a name that means Little Valley behind the Hills. Arlee is known as Nɫq̓alq͏ʷ, meaning Place of Wide-diameter Trees (although this referred to unusually large aspens, not ponderosas). Schley is called Snɫaʔpcnálq͏ʷ, meaning Coming to the Edge of the Forest, referring to the clear, fire-maintained border between the large open forests of the Schley area and the open Jocko Valley. Valley Creek is called Ɫq͏ʷq͏ʷeʔúlex͏ʷ, meaning Corner of a Valley. The area near Ronan where many traditional Pend d’Oreille people live is called Nm̓l̓á Sewɫk͏ʷs, meaning Raven’s Waters. It was precisely because these are culturally important places—because they have long been heavily used areas that were more intensively managed with fire—that they were also home to such tremendous forests.

And by the same token, the wholesale leveling of those trees was particularly traumatic for the traditional native communities of the Flathead Reservation. Nothing could have more powerfully communicated the utter political powerlessness of tribal people in the early twentieth century than the logging off of these ponderosa cathedrals, these places most magnificently shaped by the traditional use of fire.

Smokey the Bear and Chief Charlo, l to r back row: Susette Charlo, Chief Paul Charlo, Clarence Sonny Whitworth, Smokey, M.L. "Ozzie" Osborn (BIA forest manager); front row: Alexander "Sam" Clairmont, Walter McDonald (CSKT tribal chairman), Forrest Stone (BIA Superintendent)

If the decades after 1910 were the nadir of tribal political power on the Flathead Reservation, the regaining of meaningful sovereignty began in 1934, when Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act. The IRA, or Wheeler-Howard Act, was part of the sweeping legislative reforms comprising Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal—an ambitious set of federal initiatives aimed at alleviating the crushing poverty of the Great Depression. Much of the New Deal was motivated by a burning sense of the injustice of people living in utter destitution in the richest nation on earth, and the IRA was no exception. FDR’s Commissioner of Indian Affairs was John Collier, who in the 1920s had led the American Indian Defense Association. Collier was a fierce critic of what he saw as the corruption, negligence, and paternalism of federal Indian policy, and he had long advocated for far-reaching changes—most fundamentally in supporting self-governance for tribal nations. The IRA implemented a number of those reforms. It put an end to the allotment act and the loss of tribal lands. It also allowed tribes the option to incorporate and govern themselves through an elected council, modeled after American forms of representative democracy, that would be formally recognized by the U.S. government.

Yet even as the IRA provided for new levels of self-governance, it also forced tribes to abandon their older traditional structures of leadership and power. In 1935, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes became the first tribe in the U.S. to adopt the provisions of the IRA. In accepting the new tribal constitution, the tribes did gain, as elder Charlie McDonald often said, a much stronger voice in advocating for their sovereignty. But ironically, they simultaneously were forced to accept the official dissolution of their traditional chiefs. Chief Martin Charlo of the Salish and Chief Koostahtah of the Kootenai were to become honorary members of the first tribal council, but upon their deaths, the tribes would have no more chiefs. The chiefs of the Pend d’Oreilles and Camas Prairie Kalispels were omitted altogether from the new council. Many “full bloods” felt that the new system only gave more entrenched power to “mixed bloods” who were more conversant in white power structures and more able to use the system for their own benefit.

The IRA, in short, set in motion a complicated interplay between the tribe’s reassertion of political sovereignty and the struggle for cultural survival. This dynamic played out in many policy areas, including forest management and fire control. On the one hand, the newly constituted tribal government was now better able to scrutinize BIA activities on the reservation, including the forestry program. Tribal council sessions frequently focused on the extent of logged over lands, and on the need to replant areas that were not regenerating on their own. But on the other hand, the tribal members who generally controlled the council also tended to be more acculturated in a number of areas, including the role of fire. When the council addressed fire, it was usually over how to obtain more federal funding for more effective suppression efforts.

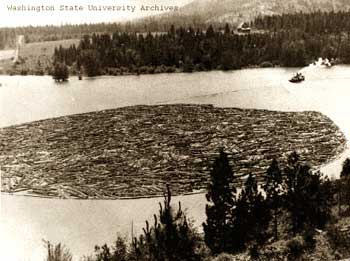

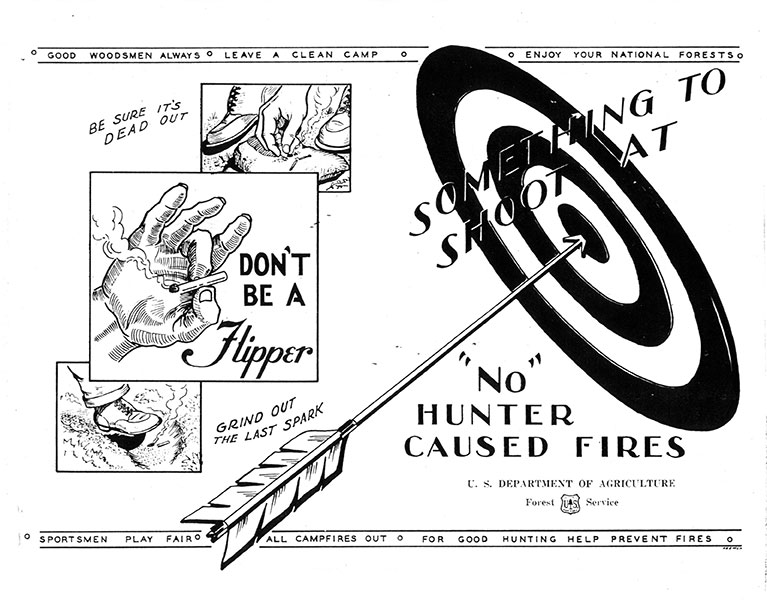

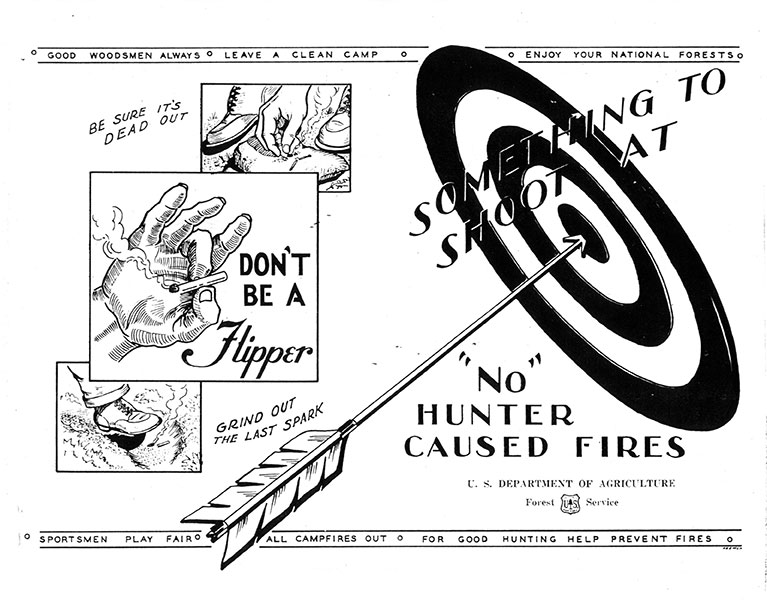

Fire prevention poster circulated on the reservation circa 1950.

On the Flathead Reservation, the Civilian Conservation Corps employed hundreds of tribal members, many in building forest roads, constructing and manning lookout towers, and fighting fires. A 200-man camp was established in the Jocko River canyon, and a 100-man camp along Mill Creek near Niarada. Among other projects, the Jocko camp built the Jocko lookout, the South Fork of the Jocko truck trail, the Jocko Lakes truck trail, the Pistol Creek truck trail, the St Mary’s Lake road, and the Jocko River road. Among the projects completed by the Mill Creek camp were the Mill Creek truck trail, the Mill Creek road, the Mill Pocket Creek truck trail, and the Bassoo Creek truck trail.ix Pend d’Oreille elder John Peter Paul recalled doing this work with other traditional people, including Mitch Smallsalmon. At one point, John served as a crew boss overseeing CCC fire-fighters—most of them city boys with no experience in the West or in working on fires—in the Hog Heaven area at the north end of the reservation. John remembered the fear many of them had of the numerous rattlesnakes in the area.

The CCC program, the new IRA government, and the New Dealers now in charge of BIA operations on the Flathead Reservation were all dedicated to fire suppression. As Pend d’Oreille elder Michael Louis Durglo, Sr. has observed, “the Forestry Department put a stop to where you could burn. Instead of using the fire as a tool, you know, they kind of look at it, the fire is like a enemy anymore. To us Indian people, we use that as a tool. So every time we go see a fire out there they're all out there rushing out there to put it out.”

Salish elder Eneas Vanderburg agrees: “They don't allow burning anymore all these places. Any kind of little fire starts now, well, they're up there and they put it out. Don't even go a couple acres. So that...doesn't take care of the underbrush....You can't even see 20, 30 feet around wherever you walk in the timber. It's just full of brush.”

The transformation of the reservation landscape is evident everywhere. In 1900, the Ronan postmistress complained to government officials about Indians in the Mission Mountains due east of her town picking huckleberries and lighting fires. She was in fact observing Pend d’Oreille people utilizing—and helping regenerate—some particularly well-known and preferred picking areas. That kind of burning was subsequently suppressed for most of the twentieth century; Tony Incashola recalls going back to that very area in the 1970s with his maternal grandmother: "In the…early '70s, just about before my grandmother passed away, she wanted to go berry picking. It was in late August, she wanted to go to the Mission at the foot of the hills where one of her traditional areas as a family she would go up and pick the huckleberries, and she wanted to go up there again. And she knew the spot that she always wanted to.

Flathead Reservation CCC personnel erecting the Ever Fire Lookout in May 1939. Photo courtesy CSKT Forestry Dept. with thanks to Roiann Matt.

Agnes Woodcock Indashola (1883-1978). Photo courtesy Tony Incashola, personal collection. All rights reserved.

"And after a while she just gave up and she—we sat there for a while on horse, and she almost cried she was so sad to see that all the areas that were part of her life, picking berries and gathering plants, she couldn't get to anymore. And in a sense that was part of her life that was being taken from her, that she was not able to do anymore.

"And being at that age when the elders go back and as they see their friends and their families passing away and disappearing, these areas become even more important to them because they can go back not only to pick the berries that they need and that they love to eat, but also to go back and be in contact with their past, with the areas that they shared with their families, with their loved ones. And that brought sadness to her because she wasn't able to go there anymore."

Even as fire suppression was intensifying, some reservation officials also began to offer an emerging critique of the rapacious logging of the reservation’s old growth during the 1910s and 1920s. In 1937, BIA Forestry produced a report on “Logged Over Ponderosa Pine Lands” that detailed the extent of damage done—not only by the immense clearcuts, but also, according to the authors, by “repeated” fires in the cut over areas. The result were vast areas, once forested with huge trees, now almost devoid of any cover. The Evaro district, which “originally grew a very excellent forest, consisting principally of ponderosa pine in pure stands,” would take “centuries” to regenerate. In the once heavily timbered Valley Creek district, “nothing remains on the ridge tops and south slopes but the stumps.” In the Mission Range district, “the natural reestablishment of the forest cover over the greater part of these lands will require centuries of time.”x

In October 1938, Director of Forestry Lee Muck followed up the 1937 report by advocating the implementation of sustainable yield forestry at Flathead. Muck estimated there was a total of 900 million board feet on the reservation, and he suggested that 1%—just 9 million board feet—should be cut per year, thus allowing for a 100-year cycle of tree harvesting. Traditional elders might have supported Muck, but his peers in tribal governance did not. BIA Range Supervisor Donald opposed the 9 million board feet limitation, and Forest Supervisor C.D. Faunce took no action.xi In 1944, the Forestry program was reporting to the Agency Superintendent that although “a large volume of timber has been cut from the Flathead Reservation during the last 25 or 30 years….there still remains a considerable volume to be cut on a sustained yield basis.” Where Muck had estimated that reservation forests held a total of 900 million board feet, his successor, J.D.Lamont, now claimed almost double that amount -- “1,658,700,000 feet of saw timber.” And Lamont stressed the need for “considerable funds and personnel for presuppression and suppression purposes.”xii

The same expression of dissent—and overruling of dissent—was happening at the same time at the national level. At the 1935 convention of the Society of American Foresters, Professor H.H. Chapman of the Yale School of Forestry held a session that—for the first time in a high-level, public setting in nearly three decades—invited open challenging of the conventional wisdom on fire. Critiques and doubts erupted during the session. Among those most forcefully advocating for a radical revision of fire policy was Eelers Koch, a ranger on the Flathead National Forest who had served in the thick of the 1910 fires and had then worked for decades on making sure it didn’t happen again. As historian Stephen Pyne has written, Koch “now regarded ‘the whole history of the Forest Service’s attempt to control fire in the backcountry of the Selway and Clearwater’ as ‘one of the saddest chapters in the history of a high-minded and efficient public service.’ Despite ‘heroic effort,’ the country remained ‘swept again and again by the most uncontrollable conflagrations.’ In 1934, despite thousands of firefighters and unlimited dollars, crews had made no better progress than in 1910.” Koch had the courage to face the obvious truth—“the unquestionable fact that the country is in worse shape now than when we took charge of it.”xiii

Chapman’s revolutionary session at the SAF convention would bear fruit—but not for a very, very long time. Just as Lee Muck’s appeal for sustainable practices was shunted aside at Flathead, so the calls of Eelers Koch and others for a new fire policy were ignored in the US Forest Service. Indeed, beginning that same year, federal fire suppression efforts became far more ambitious. In April 1935, Chief Forester Ferdinand Augustus Silcox announced the 10 AM policy, which set the goal in every forest in the country that fires of any size and in any location were to be controlled by 10 AM the following day. This directive would govern national fire policy for decades.xiv

No agency would develop any differing policy until 1968, when the National Park Service began allowing some limited burning of lightning caused fires. Ten years later, the Forest Service began doing the same thing in some designated wilderness areas. By 1995, the agency’s policy had evolved to a position of suppressing bad fires and promoting good ones.

The emphasis on fire-fighting was always tied to the commodification of the forests, and in the middle decades of the twentieth century, the Forest Service became an agency less dedicated to safeguarding the nation’s resources than to protecting and delivering raw materials to the timber industry. As environmental historian Paul Hirt has pointed out, before World War II, 95% of the nation’s lumber came from private land. It was only after the war that the Forest Service began opening huge tracts of forest to industrial harvest. Between 1945 and 1960, over 65,000 miles of logging roads were built in the National Forests. Agency employment jumped from 4,000 in 1938 to 18,000 by 1955. During the 1950s, production soared from 3.5 billion board feet to 9.3 billion board feet per year.xv On the Flathead Reservation, despite years of appeals by tribal elders to put a stop to clearcutting, this remained the predominant method for many years.

During the same post-war period, the pace of tribal cultural loss was quickening. The IRA stopped but did not reverse the effects of the allotment act; most of the best land on the reservation remained in white ownership, most of the population was white, and now tribal children were attending public schools where they were a minority. The tribal way of life was further buffeted by industrial development, and then the enormous social dislocations of World War II. The result was a rapid loss of the cultural identity of the tribes, perhaps most tellingly reflected in the dramatic changes in native language retention. Almost all tribal members born before the opening of the reservation in 1910 were fluent in at least one of the native languages; perhaps fewer than 10% of tribal members born after World War II could speak either Salish or Kootenai.

Yet even as traditional Salish-Pend d’Oreille culture was in steep decline, and even as the great trees of the Flathead Reservation were being felled by chainsaws, the seeds of rebirth and recovery were being planted -- in some sense the delayed result of the movement toward tribal sovereignty begun by the IRA in 1934. Now, the idea of political self-rule was being gradually reconnected to the revitalization of traditional culture. During the 1970s, Congress passed a number of bills such as the American Indian Self- Determination and Education Assistance Act that the tribes used to expand their governmental operations, particularly in the area of natural resource management. At the same time, a number of elders and interested younger people, alarmed by the loss of cultural knowledge, organized to form Salish-Pend d’Oreille and Kootenai culture committees, dedicated to recording and teaching the language and traditional knowledge. The natural resource department developed at the same time, reflecting a renewed respect for traditional cultural perspectives, particularly in the area of environmental understanding.

Yet through the 1980s and much of the 1990s, the Forestry Department remained somewhat insulated from these changes. Part of the reason was certainly that logging continued to be one of the few steady sources of hard dollars for the tribes, bringing in millions in income and generating many high-paying jobs. And part of the reason was that it was one of the last tribal departments to be taken over directly by the tribal government. Until 1995, Forestry remained under the control of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The takeover of the forestry program by the Tribal government impelled a comprehensive reassessment of forestry—and the use of fire—on the Flathead Reservation. In May 2000, after many months of study and meetings involving a wide range of tribal members, from professional foresters to traditional elders, the governing tribal council unanimously adopted a new management plan that in many ways stood as a revolutionary departure from previous policies. No longer would commodity lumber production be the primary driving force. The new plan put a premium on “the restoration of pre-European forest conditions,” with that goal being balanced “with the needs of sensitive species and human uses of the forest.” Where logging continued, it would now “mimic natural disturbances as much as possible.”

And once again, fire would be returned to the landscape in a widespread, systematic fashion: “Silvicultural treatments would be designed to reverse the effects of fire exclusion and undesirable forest practices of the past. Prescribed fire would be a major tool.” The new CSKT forest plan was informed by a new awareness of the environmental history of the region—a realization that while the state of the forests of the Northern Rockies had changed dramatically in the twentieth century, their basic ecology had not. The woods of Salish and Pend d’Oreille territory had evolved with fire, and they would always need fire. No matter how large and sophisticated the fire-fighting operations became, these forests would burn, sooner or later. The only question was when, and in what manner. The aggressive fire suppression measures implemented by both federal and tribal agencies, as it turned out, had only ensured that the trees would become crowded and diseased. Now, when the flames did come, the fire would be far more destructive and far less beneficial.

All of these lessons were an implicit part of the new forest plan. Once again, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes were offering a model for the careful and wise stewardship of western forests that necessarily involved an expanded use of fire. In coming years, we will see how this plays out on the ground -- and in the woods. If the goals of the new forest plan are thoroughly implemented, the story of native people, fires, and forests in the northern Rockies will have come full circle. As Tony Incashola, the Director of the Salish-Pend d’Oreille Culture Committee, puts it, “we need to keep in mind as we go forward here to reintroduce fire, the reason we're doing it…to retain a culture, is to retain a way of life…look back to the mountains…Our religion is up there, our prayers. Everything that is as important to traditional people is there.”

__________________

i United States Court of Claims, The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the FlatheadReservation, Montana, v. The United States, No. 50233, Jan. 22, 1971, as amended April 23, 1971. 437 F.2d 458, 193 Ct.Cl. 801. Cowen, Chief Judge; Laramore, Durfee, Davis, Collins, Skelton, and Nichols, Judges; Harry E. Wood, Trial Commissioner. Quote is from Opinion of Harry E. Wood, Trial Commissioner, IV (d) p 9. In the Per Curiam, the judges state, “The court agrees with the trial commissioner’s recommended opinion of law and with his findings of fact which are adopted.”

ii Historical Research Associates (Missoula, Montana), Timber, Tribes, and Trust: A

History of BIA Forest Management on the Flathead Indian Reservation (1855-1975) (Dixon, MT: Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, 1977), 69 and 71. The book alternately states the 1920 figure as 53 or 598 million board feet.

iii Annual Reports of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office), 1906: 90-91, 1907: 71-72, 1908: 57.

iv Timber, Tribes, and Trust, 50-51. The book erroneously states that this was the first substantial commercial sale authorized by the government on the reservation. See above, FN 3.

v Timber, Tribes, and Trust, 50-51, 61, 76.

vi For years, this area had been known to government officials and logging interests. In 1891, for example, US Indian Agent Peter Ronan wrote, “on Crow Creek....excellent timber of white pine Tamerac and fir grow in the surrounding country and extends far back into the mountains in almost inexhaustible quantities.” Ronan to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1891. National Archives, Washington, D.C., Record Group 75 (Bureau of Indian Affairs), Letter Received by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1881-1907, document number 1891-25090.

viiTimber, Tribes, and Trust, 62-64. Other major timber sales during the period included the Heron Lumber Co (Edward Donlan), 24 million board feet logged in the Camas Creek Unit in 1919; Henry Matt, 46 million board feet logged in the Lower Frog area near Schley in 1921; and the Dewey Lumber Co., 49 million board feet logged in the Big Arm area in 1923. Ibid, pp. 69, 76-77.

viii Supt. Charles Coe to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Sept. 9, 1924, National Archives and Records Administration, Rocky Mountain Regional Branch, Denver, Record Group 75 (Bureau of Indian Affairs), Flathead Agency Files, 8NS-075-96-320, Box 10, Misc Letters 1910-1925, folder 5x - FRC 26641. Forest Guard to Supt. Theodore Sharp, 1917, quoted in Timber, Tribes, and Trust, 63.

ix Timber, Tribes, and Trust, 91.

x “Report on Logged Over Ponderosa Pine Lands,” National Archives and Records Administration, Rocky Mountain Regional Branch, Denver. Record Group 75 (Bureau of Indian Affairs), Flathead Agency Files, Box 299 -- “Correspondence & Reports -- Fire, Weather, Training, 1920-1950.”

xi Timber, Tribes, and Trust, 97.

xii Acting Director of Forestry J.D. Lamont to Supt. Coulsen C. Wright, June 21, 1944, National Archives and Records Administration, Rocky Mountain Regional Branch, Denver, Record Group 75 (Bureau of Indian Affairs), Flathead Agency Files, Box 64, “Special Indian Office Letters.”

xiii Stephen Pyne, Year of the Fires: The Story of the Great Fires of 1910 ( New York: Viking, 2001), 265-

266. Pyne notes that Koch felt the building of roads was not only tied to an impractical, ultimately futile

attempt to suppress fire, but was also destroying the backcountry. See his essay “The Passing of the Lolo

Trail,” in his book, Forty Years a Forester (Missoula, Mountain Press, 1998).

xiv Pyne, 267-268.

xv Paul Hirt, A Conspiracy of Optimism: Management of the National Forests Since

World War II (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994).

Along with the Great Fires of 1910, the opening of the Flathead Reservation to non-Indian settlement led to the near total elimination of tribal traditions of burning the land. It also helped usher in a non-Indian approach to forestry.

The Photos Below

With the exception of the first photo, Logs on Lake Pend Oreille, all of the photographs in this series are from: "Report on Logged-Over Ponderosa Pine Lands on the Flathead Indian Reservation, Montana", by Harold Weaver. At the time of the report (1937), it had long been "a matter of common knowledge that large areas of what was originally excellent forest lands on the Flathead Reservation had been denuded" of all trees by aggressive logging and subsequent fires that consumed any regeneration. The report was done to document the need for replanting. Use the navigation bubbles at the bottom of the photo to move through the photos.

The Photos Below

With the exception of the first photo, Logs on Lake Pend Oreille, all of the photographs in this series are from: "Report on Logged-Over Ponderosa Pine Lands on the Flathead Indian Reservation, Montana", by Harold Weaver. At the time of the report (1937), it had long been "a matter of common knowledge that large areas of what was originally excellent forest lands on the Flathead Reservation had been denuded" of all trees by aggressive logging and subsequent fires that consumed any regeneration. The report was done to document the need for replanting. Use the navigation bubbles at the bottom of the photo to move through the photos.

In 1910, two cataclysmic events forever transformed the economy and ecology of the Flathead Indian Reservation. One was the Great Fires of August, which swept across the heart of Salish-Pend d’Oreille territory, and subsequently led to the dramatic expansion of fire suppression efforts across the American West. The other was the Congressionally mandated opening of the Flathead Reservation to non-Indian settlement—an abrogation of the Hellgate Treaty of 1855, which had “reserved” the area for the “exclusive use and benefit” of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. Both of these events led to the further marginalization of tribal ways of life, and the near total elimination of tribal traditions of burning the land. And both helped bring the prevailing non-Indian approach to forestry—a combination of fire suppression and heavy logging of old-growth timber—onto the reservation itself.

The opening of the reservation to non-Indian settlement was accomplished through the Flathead Allotment Act, a legislative spin-off of the General Allotment Act or Dawes Severalty Act passed by Congress in 1887. The Dawes Act set up the basic policy of allotment—a scheme that broke up communally-held tribal lands into tracts assigned to individual Indians, and then declared any remaining lands within the reservation to be “surplus” and threw them open to non-Indian homesteaders. Because each reservation was established by a specific treaty with specific language regarding lands and tribal sovereignty, Congress had to pass separate bills applying the General Allotment Act to the various reservations in the years after 1887.

Sam Resurrection

For Indian people, allotment was perhaps the single most devastating piece of legislation in U.S. history. In 1887, American Indian people controlled a total of some 138 million acres; by 1934, when FDR’s Indian Reorganization Act finally put an end to the policy, their lands had been reduced to 48 million acres—a loss of 90 million acres, two-thirds of the native landbase in 1887—a landbase that was already radically reduced from its original extent. The Allotment Act continues to play a powerful role today in the socioeconomic depression and cultural loss besetting many tribes across the country.

On the Flathead Reservation, the effects of allotment were as dramatic and as damaging as anywhere in the nation. Between 1910 and 1929, 409,710 acres of the reservation’s best agricultural lands were made available to homesteaders. Between 1910 and 1935, another 131,239 acres of original Indian allotments were transferred into fee patent status, with nearly all eventually sold to non-Indians. Many of the sales were forced upon Indians by federal agents helping storeowners and others cash in small debts. Tens of thousands of additional acres were seized by the government to build townsites, create “villa sites” on Flathead Lake for generally wealthy vacation-home builders, establish a 16,000-acre National Bison Range, support public schools, build roads, construct dams and canals for irrigation, establish research stations for the University of Montana, and other purposes. Federal maps for a while referred to the area as the “former Flathead Indian Reservation.”

Joseph Dixon

Until 1910, the Flathead Reservation was still a largely native world, with few non- Indians, few fences, and fewer roads. The only businesses legally operating within the reservation were licensed Indian traders, and many of them were forced to learn at least one of the native languages in order to operate successfully. All that changed overnight. From 1910 on, the best land and the economy as a whole were firmly controlled by non- Indians. Now it was Indian people who had to learn English in order to make a living. The opening of the reservation to white settlement had accomplished in a few months the kind of cultural change that Jesuit boarding schools could not effect in 30 years. Gradually increasing numbers of Indian parents stopped teaching their children how to speak Salish and Kootenai, because they felt that in this new world, traditional linguistic and cultural knowledge would be more of an impediment than an asset.

The further marginalization of tribal ways of life meant the near elimination of the traditional use of fire. As we have seen, federal Indian policies in the late nineteenth century had already made it difficult for tribal people to burn, even within the bounds of the reservation. Now it was nearly impossible, with the majority of the reservation’s population comprised of non-Indians, their newly established towns and ranches sprinkled across the Mission and Jocko valleys. Tribal people could continue to use tribal lands for hunting, fishing, and gathering roots, berries, and medicines. But burning became a much more difficult—much riskier—proposition.

The rising economic and political power of non-Indians on the reservation was aided by the lack of any effective countervailing tribal governmental structure. For years, the traditional chiefs had been undermined by U.S. agents and superintendents. After the opening of the reservation, Superintendent Frederick Morgan established a Flathead Business Committee, consisting mainly of mixed bloods and whites married to tribal members. They served as little more than a rubber stamp for BIA policies. Over the next two decades, various groups arose, each claiming to be the legitimate government of the tribe. All sought the approval of the traditional "full bloods," and on numerous occasions, the traditional leaders were manipulated into signing documents they didn't understand.

Polley Lumber Co. loading logs

Beginning in the 1880’s, the Northern Pacific Railroad had logged extensively within its 56-mile-long, 200-foot right-of-way in the southern portion of the reservation, and apparently also committed numerous acts of timber trespass on adjoining tribal lands. But other than the NPRR logging, the federal government allowed no commercial or large-scale timber harvests within the reservation prior to 1900.

Between the turn of the century and 1910, the government did approve a few salvage sales, some of considerable size. In 1907-09, nearly twenty million board feet of “dead and downed” timber were logged under special authorization from the Office of Indian Affairs – over eight million board feet in the Post Creek district by the John O’Brien Lumber Company of Somers and over nine million board feet in the Evaro-Jocko district by Edward Donlan and W.B. Russell of Missoula.iii Soon after, in the wake of the 1910 fires, the government sold about three million board feet of burned timber, mostly in the Rocky Point area on the west shore of Flathead Lake, to the Cramer Lumber Company.iv Even those sales, however, were minuscule compared to what would follow in the next two decades, particularly in the southern end of the reservation, home to the most massive old growth ponderosa pines—the product of centuries of systematic traditional fire management using frequent low-intensity burns.

In 1917, two enormous sales were executed in the southern end of the reservation. The Polley Lumber Company logged over 46 million board feet in the Schley and Arlee areas. And the Heron Lumber Company, headed by Edward Donlan, clearcut almost 62 million board feet of mature pure ponderosa stands in the Evaro area. In 1923, Heron Lumber would cut an even bigger swath in the Valley Creek area, harvesting a staggering 146 million board feet. Tribal elder Harriet Whitworth, who was born in 1918 and grew up in Valley Creek, remembers the heartbroken feeling among many Salish people as the great trees were knocked down and hauled out. The creek itself, a teeming trout fishery, completely dried up for a period of time after the trees were removed.v

On the reservation as elsewhere in western Montana, this industrial scale of exploitation of natural resources was directly connected to the development of critical infrastructure—and in particular, railroads. Railroads enabled the conversion of raw natural materials—logs, copper, wheat, livestock -- into marketable commodities, linked by the steel roads to regional, national, and international markets. The logging of Evaro, Arlee, and Valley Creek was made possible by the proximity of those units to the mainline of the Northern Pacific Railroad.

The reach of the railroad on the Flathead Reservation was extended further in 1916, when the Northern Pacific secured from the government approval—and right-of-way—to build a spur line from Dixon north to Polson, thus bringing the Mission Valley into the orbit of the markets. In 1917, the railroad was built, and that same year, the Polley Lumber Company began intensive harvesting of the gigantic ponderosas near Ronan, at the western base of the Mission Mountains.vi Between the forests and the Dixon-Polson line, Polley built small-gauge railroads to haul the out trees, many of which were so enormous that just one log took up an entire rail car. Between 1917 and 1928, Polley cut 108 million board feet in the area.vii

Each of these areas—Evaro, Arlee, Schley, Valley Creek, and also further north in the Ronan area of the Mission Valley—is an ancient traditional center of population for Pend d’Oreille (and in more recent years, Salish) people. Evaro is called Snɫl̓ʔoy̓čô, a name that means Little Valley behind the Hills. Arlee is known as Nɫq̓alq͏ʷ, meaning Place of Wide-diameter Trees (although this referred to unusually large aspens, not ponderosas). Schley is called Snɫaʔpcnálq͏ʷ, meaning Coming to the Edge of the Forest, referring to the clear, fire-maintained border between the large open forests of the Schley area and the open Jocko Valley. Valley Creek is called Ɫq͏ʷq͏ʷeʔúlex͏ʷ, meaning Corner of a Valley. The area near Ronan where many traditional Pend d’Oreille people live is called Nm̓l̓á Sewɫk͏ʷs, meaning Raven’s Waters. It was precisely because these are culturally important places—because they have long been heavily used areas that were more intensively managed with fire—that they were also home to such tremendous forests.

And by the same token, the wholesale leveling of those trees was particularly traumatic for the traditional native communities of the Flathead Reservation. Nothing could have more powerfully communicated the utter political powerlessness of tribal people in the early twentieth century than the logging off of these ponderosa cathedrals, these places most magnificently shaped by the traditional use of fire.

Smokey the Bear and Chief Charlo

If the decades after 1910 were the nadir of tribal political power on the Flathead Reservation, the regaining of meaningful sovereignty began in 1934, when Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act. The IRA, or Wheeler-Howard Act, was part of the sweeping legislative reforms comprising Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal—an ambitious set of federal initiatives aimed at alleviating the crushing poverty of the Great Depression. Much of the New Deal was motivated by a burning sense of the injustice of people living in utter destitution in the richest nation on earth, and the IRA was no exception. FDR’s Commissioner of Indian Affairs was John Collier, who in the 1920s had led the American Indian Defense Association. Collier was a fierce critic of what he saw as the corruption, negligence, and paternalism of federal Indian policy, and he had long advocated for far-reaching changes—most fundamentally in supporting self-governance for tribal nations. The IRA implemented a number of those reforms. It put an end to the allotment act and the loss of tribal lands. It also allowed tribes the option to incorporate and govern themselves through an elected council, modeled after American forms of representative democracy, that would be formally recognized by the U.S. government.

Yet even as the IRA provided for new levels of self-governance, it also forced tribes to abandon their older traditional structures of leadership and power. In 1935, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes became the first tribe in the U.S. to adopt the provisions of the IRA. In accepting the new tribal constitution, the tribes did gain, as elder Charlie McDonald often said, a much stronger voice in advocating for their sovereignty. But ironically, they simultaneously were forced to accept the official dissolution of their traditional chiefs. Chief Martin Charlo of the Salish and Chief Koostahtah of the Kootenai were to become honorary members of the first tribal council, but upon their deaths, the tribes would have no more chiefs. The chiefs of the Pend d’Oreilles and Camas Prairie Kalispels were omitted altogether from the new council. Many “full bloods” felt that the new system only gave more entrenched power to “mixed bloods” who were more conversant in white power structures and more able to use the system for their own benefit.

The IRA, in short, set in motion a complicated interplay between the tribe’s reassertion of political sovereignty and the struggle for cultural survival. This dynamic played out in many policy areas, including forest management and fire control. On the one hand, the newly constituted tribal government was now better able to scrutinize BIA activities on the reservation, including the forestry program. Tribal council sessions frequently focused on the extent of logged over lands, and on the need to replant areas that were not regenerating on their own. But on the other hand, the tribal members who generally controlled the council also tended to be more acculturated in a number of areas, including the role of fire. When the council addressed fire, it was usually over how to obtain more federal funding for more effective suppression efforts.

Fire prevention poster circa 1950

On the Flathead Reservation, the Civilian Conservation Corps employed hundreds of tribal members, many in building forest roads, constructing and manning lookout towers, and fighting fires. A 200-man camp was established in the Jocko River canyon, and a 100-man camp along Mill Creek near Niarada. Among other projects, the Jocko camp built the Jocko lookout, the South Fork of the Jocko truck trail, the Jocko Lakes truck trail, the Pistol Creek truck trail, the St Mary’s Lake road, and the Jocko River road. Among the projects completed by the Mill Creek camp were the Mill Creek truck trail, the Mill Creek road, the Mill Pocket Creek truck trail, and the Bassoo Creek truck trail.ix Pend d’Oreille elder John Peter Paul recalled doing this work with other traditional people, including Mitch Smallsalmon. At one point, John served as a crew boss overseeing CCC fire-fighters—most of them city boys with no experience in the West or in working on fires—in the Hog Heaven area at the north end of the reservation. John remembered the fear many of them had of the numerous rattlesnakes in the area.

The CCC program, the new IRA government, and the New Dealers now in charge of BIA operations on the Flathead Reservation were all dedicated to fire suppression. As Pend d’Oreille elder Michael Louis Durglo, Sr. has observed, “the Forestry Department put a stop to where you could burn. Instead of using the fire as a tool, you know, they kind of look at it, the fire is like a enemy anymore. To us Indian people, we use that as a tool. So every time we go see a fire out there they're all out there rushing out there to put it out.”

Salish elder Eneas Vanderburg agrees: “They don't allow burning anymore all these places. Any kind of little fire starts now, well, they're up there and they put it out. Don't even go a couple acres. So that...doesn't take care of the underbrush....You can't even see 20, 30 feet around wherever you walk in the timber. It's just full of brush.”

The transformation of the reservation landscape is evident everywhere. In 1900, the Ronan postmistress complained to government officials about Indians in the Mission Mountains due east of her town picking huckleberries and lighting fires. She was in fact observing Pend d’Oreille people utilizing—and helping regenerate—some particularly well-known and preferred picking areas. That kind of burning was subsequently suppressed for most of the twentieth century; Tony Incashola recalls going back to that very area in the 1970s with his maternal grandmother: "In the…early '70s, just about before my grandmother passed away, she wanted to go berry picking. It was in late August, she wanted to go to the Mission at the foot of the hills where one of her traditional areas as a family she would go up and pick the huckleberries, and she wanted to go up there again. And she knew the spot that she always wanted to.

Erecting Evaro fire lookout in 1939.

Agnes Woodcock Incashola

"And after a while she just gave up and she—we sat there for a while on horse, and she almost cried she was so sad to see that all the areas that were part of her life, picking berries and gathering plants, she couldn't get to anymore. And in a sense that was part of her life that was being taken from her, that she was not able to do anymore.

"And being at that age when the elders go back and as they see their friends and their families passing away and disappearing, these areas become even more important to them because they can go back not only to pick the berries that they need and that they love to eat, but also to go back and be in contact with their past, with the areas that they shared with their families, with their loved ones. And that brought sadness to her because she wasn't able to go there anymore."

Even as fire suppression was intensifying, some reservation officials also began to offer an emerging critique of the rapacious logging of the reservation’s old growth during the 1910s and 1920s. In 1937, BIA Forestry produced a report on “Logged Over Ponderosa Pine Lands” that detailed the extent of damage done—not only by the immense clearcuts, but also, according to the authors, by “repeated” fires in the cut over areas. The result were vast areas, once forested with huge trees, now almost devoid of any cover. The Evaro district, which “originally grew a very excellent forest, consisting principally of ponderosa pine in pure stands,” would take “centuries” to regenerate. In the once heavily timbered Valley Creek district, “nothing remains on the ridge tops and south slopes but the stumps.” In the Mission Range district, “the natural reestablishment of the forest cover over the greater part of these lands will require centuries of time.”x

In October 1938, Director of Forestry Lee Muck followed up the 1937 report by advocating the implementation of sustainable yield forestry at Flathead. Muck estimated there was a total of 900 million board feet on the reservation, and he suggested that 1%—just 9 million board feet—should be cut per year, thus allowing for a 100-year cycle of tree harvesting. Traditional elders might have supported Muck, but his peers in tribal governance did not. BIA Range Supervisor Donald opposed the 9 million board feet limitation, and Forest Supervisor C.D. Faunce took no action.xi In 1944, the Forestry program was reporting to the Agency Superintendent that although “a large volume of timber has been cut from the Flathead Reservation during the last 25 or 30 years….there still remains a considerable volume to be cut on a sustained yield basis.” Where Muck had estimated that reservation forests held a total of 900 million board feet, his successor, J.D.Lamont, now claimed almost double that amount -- “1,658,700,000 feet of saw timber.” And Lamont stressed the need for “considerable funds and personnel for presuppression and suppression purposes.”xii

The same expression of dissent—and overruling of dissent—was happening at the same time at the national level. At the 1935 convention of the Society of American Foresters, Professor H.H. Chapman of the Yale School of Forestry held a session that—for the first time in a high-level, public setting in nearly three decades—invited open challenging of the conventional wisdom on fire. Critiques and doubts erupted during the session. Among those most forcefully advocating for a radical revision of fire policy was Eelers Koch, a ranger on the Flathead National Forest who had served in the thick of the 1910 fires and had then worked for decades on making sure it didn’t happen again. As historian Stephen Pyne has written, Koch “now regarded ‘the whole history of the Forest Service’s attempt to control fire in the backcountry of the Selway and Clearwater’ as ‘one of the saddest chapters in the history of a high-minded and efficient public service.’ Despite ‘heroic effort,’ the country remained ‘swept again and again by the most uncontrollable conflagrations.’ In 1934, despite thousands of firefighters and unlimited dollars, crews had made no better progress than in 1910.” Koch had the courage to face the obvious truth—“the unquestionable fact that the country is in worse shape now than when we took charge of it.”xiii

Chapman’s revolutionary session at the SAF convention would bear fruit—but not for a very, very long time. Just as Lee Muck’s appeal for sustainable practices was shunted aside at Flathead, so the calls of Eelers Koch and others for a new fire policy were ignored in the US Forest Service. Indeed, beginning that same year, federal fire suppression efforts became far more ambitious. In April 1935, Chief Forester Ferdinand Augustus Silcox announced the 10 AM policy, which set the goal in every forest in the country that fires of any size and in any location were to be controlled by 10 AM the following day. This directive would govern national fire policy for decades.xiv

No agency would develop any differing policy until 1968, when the National Park Service began allowing some limited burning of lightning caused fires. Ten years later, the Forest Service began doing the same thing in some designated wilderness areas. By 1995, the agency’s policy had evolved to a position of suppressing bad fires and promoting good ones.

The emphasis on fire-fighting was always tied to the commodification of the forests, and in the middle decades of the twentieth century, the Forest Service became an agency less dedicated to safeguarding the nation’s resources than to protecting and delivering raw materials to the timber industry. As environmental historian Paul Hirt has pointed out, before World War II, 95% of the nation’s lumber came from private land. It was only after the war that the Forest Service began opening huge tracts of forest to industrial harvest. Between 1945 and 1960, over 65,000 miles of logging roads were built in the National Forests. Agency employment jumped from 4,000 in 1938 to 18,000 by 1955. During the 1950s, production soared from 3.5 billion board feet to 9.3 billion board feet per year.xv On the Flathead Reservation, despite years of appeals by tribal elders to put a stop to clearcutting, this remained the predominant method for many years.

During the same post-war period, the pace of tribal cultural loss was quickening. The IRA stopped but did not reverse the effects of the allotment act; most of the best land on the reservation remained in white ownership, most of the population was white, and now tribal children were attending public schools where they were a minority. The tribal way of life was further buffeted by industrial development, and then the enormous social dislocations of World War II. The result was a rapid loss of the cultural identity of the tribes, perhaps most tellingly reflected in the dramatic changes in native language retention. Almost all tribal members born before the opening of the reservation in 1910 were fluent in at least one of the native languages; perhaps fewer than 10% of tribal members born after World War II could speak either Salish or Kootenai.

Yet even as traditional Salish-Pend d’Oreille culture was in steep decline, and even as the great trees of the Flathead Reservation were being felled by chainsaws, the seeds of rebirth and recovery were being planted -- in some sense the delayed result of the movement toward tribal sovereignty begun by the IRA in 1934. Now, the idea of political self-rule was being gradually reconnected to the revitalization of traditional culture. During the 1970s, Congress passed a number of bills such as the American Indian Self- Determination and Education Assistance Act that the tribes used to expand their governmental operations, particularly in the area of natural resource management. At the same time, a number of elders and interested younger people, alarmed by the loss of cultural knowledge, organized to form Salish-Pend d’Oreille and Kootenai culture committees, dedicated to recording and teaching the language and traditional knowledge. The natural resource department developed at the same time, reflecting a renewed respect for traditional cultural perspectives, particularly in the area of environmental understanding.

Yet through the 1980s and much of the 1990s, the Forestry Department remained somewhat insulated from these changes. Part of the reason was certainly that logging continued to be one of the few steady sources of hard dollars for the tribes, bringing in millions in income and generating many high-paying jobs. And part of the reason was that it was one of the last tribal departments to be taken over directly by the tribal government. Until 1995, Forestry remained under the control of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The takeover of the forestry program by the Tribal government impelled a comprehensive reassessment of forestry—and the use of fire—on the Flathead Reservation. In May 2000, after many months of study and meetings involving a wide range of tribal members, from professional foresters to traditional elders, the governing tribal council unanimously adopted a new management plan that in many ways stood as a revolutionary departure from previous policies. No longer would commodity lumber production be the primary driving force. The new plan put a premium on “the restoration of pre-European forest conditions,” with that goal being balanced “with the needs of sensitive species and human uses of the forest.” Where logging continued, it would now “mimic natural disturbances as much as possible.”

And once again, fire would be returned to the landscape in a widespread, systematic fashion: “Silvicultural treatments would be designed to reverse the effects of fire exclusion and undesirable forest practices of the past. Prescribed fire would be a major tool.” The new CSKT forest plan was informed by a new awareness of the environmental history of the region—a realization that while the state of the forests of the Northern Rockies had changed dramatically in the twentieth century, their basic ecology had not. The woods of Salish and Pend d’Oreille territory had evolved with fire, and they would always need fire. No matter how large and sophisticated the fire-fighting operations became, these forests would burn, sooner or later. The only question was when, and in what manner. The aggressive fire suppression measures implemented by both federal and tribal agencies, as it turned out, had only ensured that the trees would become crowded and diseased. Now, when the flames did come, the fire would be far more destructive and far less beneficial.

All of these lessons were an implicit part of the new forest plan. Once again, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes were offering a model for the careful and wise stewardship of western forests that necessarily involved an expanded use of fire. In coming years, we will see how this plays out on the ground -- and in the woods. If the goals of the new forest plan are thoroughly implemented, the story of native people, fires, and forests in the northern Rockies will have come full circle. As Tony Incashola, the Director of the Salish-Pend d’Oreille Culture Committee, puts it, “we need to keep in mind as we go forward here to reintroduce fire, the reason we're doing it…to retain a culture, is to retain a way of life…look back to the mountains…Our religion is up there, our prayers. Everything that is as important to traditional people is there.”

__________________

i United States Court of Claims, The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the FlatheadReservation, Montana, v. The United States, No. 50233, Jan. 22, 1971, as amended April 23, 1971. 437 F.2d 458, 193 Ct.Cl. 801. Cowen, Chief Judge; Laramore, Durfee, Davis, Collins, Skelton, and Nichols, Judges; Harry E. Wood, Trial Commissioner. Quote is from Opinion of Harry E. Wood, Trial Commissioner, IV (d) p 9. In the Per Curiam, the judges state, “The court agrees with the trial commissioner’s recommended opinion of law and with his findings of fact which are adopted.”

ii Historical Research Associates (Missoula, Montana), Timber, Tribes, and Trust: A

History of BIA Forest Management on the Flathead Indian Reservation (1855-1975) (Dixon, MT: Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, 1977), 69 and 71. The book alternately states the 1920 figure as 53 or 598 million board feet.

iii Annual Reports of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office), 1906: 90-91, 1907: 71-72, 1908: 57.

iv Timber, Tribes, and Trust, 50-51. The book erroneously states that this was the first substantial commercial sale authorized by the government on the reservation. See above, FN 3.

v Timber, Tribes, and Trust, 50-51, 61, 76.

vi For years, this area had been known to government officials and logging interests. In 1891, for example, US Indian Agent Peter Ronan wrote, “on Crow Creek....excellent timber of white pine Tamerac and fir grow in the surrounding country and extends far back into the mountains in almost inexhaustible quantities.” Ronan to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1891. National Archives, Washington, D.C., Record Group 75 (Bureau of Indian Affairs), Letter Received by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1881-1907, document number 1891-25090.

viiTimber, Tribes, and Trust, 62-64. Other major timber sales during the period included the Heron Lumber Co (Edward Donlan), 24 million board feet logged in the Camas Creek Unit in 1919; Henry Matt, 46 million board feet logged in the Lower Frog area near Schley in 1921; and the Dewey Lumber Co., 49 million board feet logged in the Big Arm area in 1923. Ibid, pp. 69, 76-77.

viii Supt. Charles Coe to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Sept. 9, 1924, National Archives and Records Administration, Rocky Mountain Regional Branch, Denver, Record Group 75 (Bureau of Indian Affairs), Flathead Agency Files, 8NS-075-96-320, Box 10, Misc Letters 1910-1925, folder 5x - FRC 26641. Forest Guard to Supt. Theodore Sharp, 1917, quoted in Timber, Tribes, and Trust, 63.

ix Timber, Tribes, and Trust, 91.

x “Report on Logged Over Ponderosa Pine Lands,” National Archives and Records Administration, Rocky Mountain Regional Branch, Denver. Record Group 75 (Bureau of Indian Affairs), Flathead Agency Files, Box 299 -- “Correspondence & Reports -- Fire, Weather, Training, 1920-1950.”

xi Timber, Tribes, and Trust, 97.

xii Acting Director of Forestry J.D. Lamont to Supt. Coulsen C. Wright, June 21, 1944, National Archives and Records Administration, Rocky Mountain Regional Branch, Denver, Record Group 75 (Bureau of Indian Affairs), Flathead Agency Files, Box 64, “Special Indian Office Letters.”

xiii Stephen Pyne, Year of the Fires: The Story of the Great Fires of 1910 ( New York: Viking, 2001), 265-

266. Pyne notes that Koch felt the building of roads was not only tied to an impractical, ultimately futile

attempt to suppress fire, but was also destroying the backcountry. See his essay “The Passing of the Lolo

Trail,” in his book, Forty Years a Forester (Missoula, Mountain Press, 1998).

xiv Pyne, 267-268.

xv Paul Hirt, A Conspiracy of Optimism: Management of the National Forests Since

World War II (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994).