History

The History of Fire and the Human Use of Fire in the Northern Rockies

History

The History of Fire and the Human Use of Fire in the Northern Rockies

History

The History of Fire in the Northern Rockies

After 1910, the predominant view of fire among professional foresters hardened into a nearly unanimous consensus. Now almost all of them seemed to agree that any forest fire, including “light burning,” was something wholly destructive and even morally evil.

USFS photo.

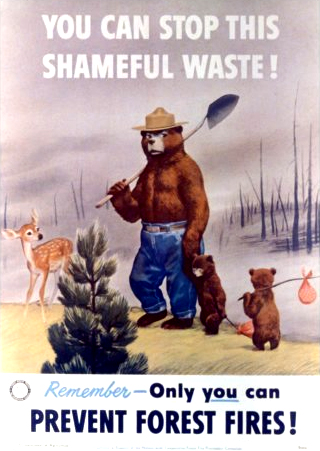

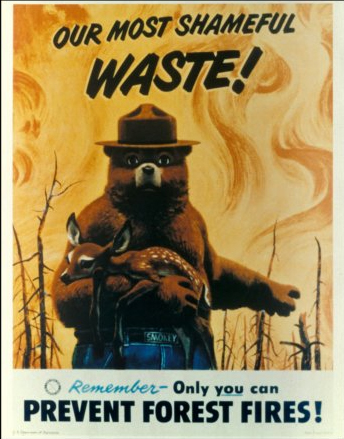

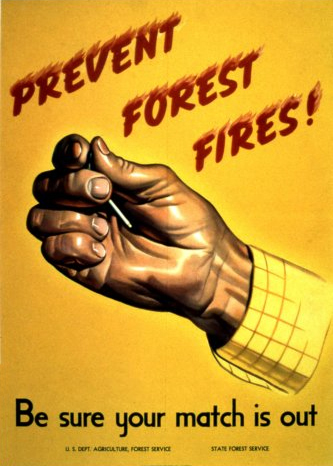

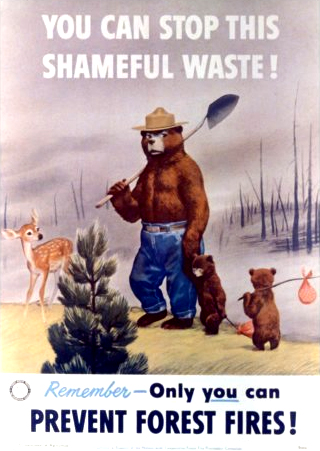

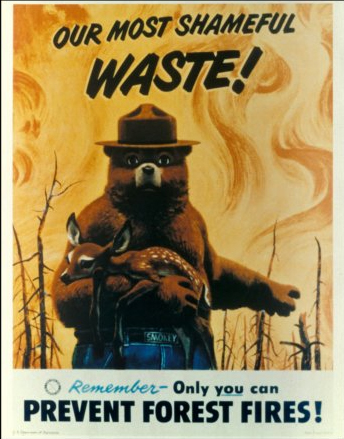

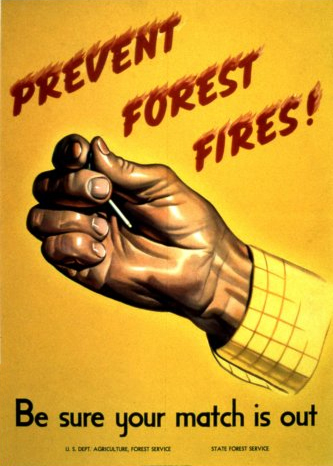

View Fire Prevention Posters from the Period

The most lasting environmental damage stemming from the Great Fires, then, came not from the flames themselves, but from the reaction of the U.S. Forest Service and other federal agencies — from the policies that became entrenched in the years and decades after 1910. Almost all foresters came to define their first and foremost responsibility as preventing fires from starting, and putting them out when they did.

They were led, or perhaps intimidated into conformity, by Gifford Pinchot. Pinchot had long anchored the “conservationist” wing of the nascent American environmental movement, which was often at odds with the “preservationist” wing and its champion, John Muir. Pinchot generally opposed removing wildlands from the reach of industry, instead advocating the ideal of sustainable harvesting of resources — a philosophy famously expressed in his mantra, “for the greatest good, for the greatest number, for the longest time.”

When Pinchot became head of President Theodore Roosevelt’s National Forest Service, he changed the name of the public woods from “forest reserves” to “national forests;” the trees would be utilized, not forever preserved. Pinchot was not only the nation’s top forester, but also one of the most prominent figures in the whole Progressive movement. He equated conservation with the Progressivism as a whole, forestry with conservation, and fire suppression with forestry. He therefore viewed any dissent on the issue of fire as an attack on this entire political project —and by extension, an attack on the welfare of the country. From a very early time, then, policy questions relating to fire and forests have been embroiled in larger political and ideological struggles, which have impeded rational discussion of the issue.i

Prior to Pinchot’s rise to power in the 1890s, there were at least moments of dissent over the issue of “light burning.” John Wesley Powell, the author of the famed Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States (1878), longtime head of the U.S. Geological Survey and the Bureau of American Ethnology, and the most prominent government authority on the western American environment, initially held a conventional view of fire and shared the usual governmental call for its general suppression. But by 1890, Powell’s observation of the dry forests of the West had apparently led him to an entirely different position. In a meeting with Secretary of the Interior John Noble, Powell made the case for letting the fires burn. He was quickly isolated, however, and his successors in the Geological Survey “denounced Indian burning, along with any other kind of fire.” .ii

Soon after Roosevelt was succeeded by William Howard Taft, Pinchot paid a price for his relentless pursuit of his own agenda and for his sometimes ruthless political style. In January 1910, he was fired for insubordination by Secretary of the Interior Richard Ballinger – a move that precipitated a split in the Republican Party, which in turn would contribute to Roosevelt running as an independent in 1912, thus dividing the vote and allowing Democrat Woodrow Wilson to win the presidency. By the time of the massive summer fires, then, Pinchot had already been removed from office by Secretary Ballinger. Nevertheless, he was still the head of the National Conservation Association, and was still able to exert far-reaching influence. Pinchot pursued a ferocious public relations campaign to ensure that the lessons taken from the Great Fires would not be any questioning of the strategy of fire suppression, but rather an enormous expansion of public dollars and infrastructure invested in the effort.

Yet for a brief time after the Great Fires, a few critics nevertheless dared offer a different analysis of the enormous blaze and the problems it exposed. At a press conference in San Francisco, Secretary Ballinger went so far as to wonder whether “We may find it necessary to revert to the old Indian method of burning over the forests annually at seasonable periods.” Pinchot responded by characterizing Ballinger and all other second-guessers as nothing less than evil allies of fire itself: the critics, he said, “have, in effect, been fighting on the side of the fires against the general welfare.” .iii

Pinchot and his allies in the Forest Service decisively won the brief argument over how best to respond to the Great Fires of 1910. The next year, Congress passed the Weeks Act, which provided federal money to states that implemented fire protection programs for timberlands at the headwaters of navigable streams. The Weeks Act was only the beginning. In the following decades, the Forest Service and other federal agencies established a vast system of lookout towers, supply lines, and command centers, organized with military discipline. Thousands of miles of roads were built through the forests, and trucks and planes gradually replaced mule trains. The fire suppression infrastructure that was created after 1910 did indeed result in more effective fire fighting. And that, in the end, was the problem – both in the aboriginal territory of the Salish and Pend d’Oreille people, and in the fire-adapted forests of the rest of the American West.

Historian Stephen Pyne has described the victory of Pinchot and the leaders of the Forest Service as “the triumph of ideology over fact.” Pyne says that they won the argument, in part, because they had on their side the weight and momentum of mainstream American culture. “When Pinchot asserted that ‘forest fires encourage a spirit of lawlessness and a disregard of property rights,’ he had centuries of European precendent behind him,” writes Pyne. “So, likewise, fire defied nature’s spirit of law and order. Fire control was thus of a piece with other conservation reforms of Progressivism: straightening stream channels; killing wolves and coyotes; fertilizing soils; draining swamps; damming rivers.” .iv

The ascendant culture of Progressivism relentlessly and vigorously pursued control over nature, and viewed accommodation with natural systems as capitulation. Implicit in this cultural logic, particularly on the issue of fire, was a racist dismissal of native people and native ways of life, a pervasive ignorance of how tribal burning of forests and grasslands was a reasonable and effective method of land management. And as we shall see in the next segment, those same assumptions shaped policy and practice on the reservation itself for most of the 20th century.

iSee Stephen Pyne, Year of the Fires: The Story of the Great Fires of 1910 (New York: Viking, 2001). Much of this chapter draws from Pyne’s fine history of the 1910 fires. On progressive conservation, see Samuel P. Hays, Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: the Progressive Conservation Movement, 1890-1920 (New York, Atheneum, 1979).

ii Pyne, p. 65.

iii Pyne, 111 and 196.

ivPyne, 114 and 80.

View Films and Newsreels from the 1920s and 1930s

These films and newsreels convey the attitude that prevailed during the first 60 to 70 years of the 20th century: Forest fires are a threat to forests and people and must be stopped regardless of the cost.

After 1910, the predominant view of fire among professional foresters hardened into a nearly unanimous consensus. Now almost all of them seemed to agree that any forest fire, including “light burning,” was something wholly destructive and even morally evil.

USFS photo.

After 1910, the predominant view of fire among professional foresters hardened into a nearly unanimous consensus. Now almost all of them seemed to agree that any forest fire, including “light burning,” was something wholly destructive and even morally evil. Only in the wake of the Great Fires were the lingering wisps of dissent stamped out, and the prevailing views set in the stone of far-reaching federal policies supported with massive funding. The result was a dramatic escalation in fire suppression in the West, including in the forests of Salish-Pend d’Oreille aboriginal territory and on the Flathead Reservation itself. The fires that swept through the tribe’s homeland, in short, had far-reaching impacts on national policies, and those policies in turn only accelerated the ecological transformation of western Montana. The vicious cycle of fire suppression and devastating fires had begun in earnest.

The most lasting environmental damage stemming from the Great Fires, then, came not from the flames themselves, but from the reaction of the U.S. Forest Service and other federal agencies — from the policies that became entrenched in the years and decades after 1910. Almost all foresters came to define their first and foremost responsibility as preventing fires from starting, and putting them out when they did.

They were led, or perhaps intimidated into conformity, by Gifford Pinchot. Pinchot had long anchored the “conservationist” wing of the nascent American environmental movement, which was often at odds with the “preservationist” wing and its champion, John Muir. Pinchot generally opposed removing wildlands from the reach of industry, instead advocating the ideal of sustainable harvesting of resources — a philosophy famously expressed in his mantra, “for the greatest good, for the greatest number, for the longest time.”

When Pinchot became head of President Theodore Roosevelt’s National Forest Service, he changed the name of the public woods from “forest reserves” to “national forests;” the trees would be utilized, not forever preserved. Pinchot was not only the nation’s top forester, but also one of the most prominent figures in the whole Progressive movement. He equated conservation with the Progressivism as a whole, forestry with conservation, and fire suppression with forestry. He therefore viewed any dissent on the issue of fire as an attack on this entire political project —and by extension, an attack on the welfare of the country. From a very early time, then, policy questions relating to fire and forests have been embroiled in larger political and ideological struggles, which have impeded rational discussion of the issue.i

Prior to Pinchot’s rise to power in the 1890s, there were at least moments of dissent over the issue of “light burning.” John Wesley Powell, the author of the famed Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States (1878), longtime head of the U.S. Geological Survey and the Bureau of American Ethnology, and the most prominent government authority on the western American environment, initially held a conventional view of fire and shared the usual governmental call for its general suppression. But by 1890, Powell’s observation of the dry forests of the West had apparently led him to an entirely different position. In a meeting with Secretary of the Interior John Noble, Powell made the case for letting the fires burn. He was quickly isolated, however, and his successors in the Geological Survey “denounced Indian burning, along with any other kind of fire.” .ii

Soon after Roosevelt was succeeded by William Howard Taft, Pinchot paid a price for his relentless pursuit of his own agenda and for his sometimes ruthless political style. In January 1910, he was fired for insubordination by Secretary of the Interior Richard Ballinger – a move that precipitated a split in the Republican Party, which in turn would contribute to Roosevelt running as an independent in 1912, thus dividing the vote and allowing Democrat Woodrow Wilson to win the presidency. By the time of the massive summer fires, then, Pinchot had already been removed from office by Secretary Ballinger. Nevertheless, he was still the head of the National Conservation Association, and was still able to exert far-reaching influence. Pinchot pursued a ferocious public relations campaign to ensure that the lessons taken from the Great Fires would not be any questioning of the strategy of fire suppression, but rather an enormous expansion of public dollars and infrastructure invested in the effort.

Yet for a brief time after the Great Fires, a few critics nevertheless dared offer a different analysis of the enormous blaze and the problems it exposed. At a press conference in San Francisco, Secretary Ballinger went so far as to wonder whether “We may find it necessary to revert to the old Indian method of burning over the forests annually at seasonable periods.” Pinchot responded by characterizing Ballinger and all other second-guessers as nothing less than evil allies of fire itself: the critics, he said, “have, in effect, been fighting on the side of the fires against the general welfare.” .iii

Pinchot and his allies in the Forest Service decisively won the brief argument over how best to respond to the Great Fires of 1910. The next year, Congress passed the Weeks Act, which provided federal money to states that implemented fire protection programs for timberlands at the headwaters of navigable streams. The Weeks Act was only the beginning. In the following decades, the Forest Service and other federal agencies established a vast system of lookout towers, supply lines, and command centers, organized with military discipline. Thousands of miles of roads were built through the forests, and trucks and planes gradually replaced mule trains. The fire suppression infrastructure that was created after 1910 did indeed result in more effective fire fighting. And that, in the end, was the problem – both in the aboriginal territory of the Salish and Pend d’Oreille people, and in the fire-adapted forests of the rest of the American West.

Historian Stephen Pyne has described the victory of Pinchot and the leaders of the Forest Service as “the triumph of ideology over fact.” Pyne says that they won the argument, in part, because they had on their side the weight and momentum of mainstream American culture. “When Pinchot asserted that ‘forest fires encourage a spirit of lawlessness and a disregard of property rights,’ he had centuries of European precendent behind him,” writes Pyne. “So, likewise, fire defied nature’s spirit of law and order. Fire control was thus of a piece with other conservation reforms of Progressivism: straightening stream channels; killing wolves and coyotes; fertilizing soils; draining swamps; damming rivers.” .iv

The ascendant culture of Progressivism relentlessly and vigorously pursued control over nature, and viewed accommodation with natural systems as capitulation. Implicit in this cultural logic, particularly on the issue of fire, was a racist dismissal of native people and native ways of life, a pervasive ignorance of how tribal burning of forests and grasslands was a reasonable and effective method of land management. And as we shall see in the next segment, those same assumptions shaped policy and practice on the reservation itself for most of the 20th century.

iSee Stephen Pyne, Year of the Fires: The Story of the Great Fires of 1910 (New York: Viking, 2001). Much of this chapter draws from Pyne’s fine history of the 1910 fires. On progressive conservation, see Samuel P. Hays, Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: the Progressive Conservation Movement, 1890-1920 (New York, Atheneum, 1979).

ii Pyne, p. 65.

iii Pyne, 111 and 196.

ivPyne, 114 and 80.

View Fire Prevention Posters from the Period

View Films and Newsreels from the 1920s and 1930s

These films and newsreels convey the attitude that prevailed during the first 60 to 70 years of the 20th century: Forest fires are a threat to forests and people and must be stopped regardless of the cost.