History

The History of Fire and the Human Use of Fire in the Northern Rockies

History

The History of Fire and the Human Use of Fire in the Northern Rockies

History

The History of Fire in the Northern Rockies

The story of the forced removal of the Salish from the Bitterroot Valley is crucial in understanding why, and how, the creation of choked, fire-vulnerable forests in western Montana really began long before the active fire suppression of the twentieth century.

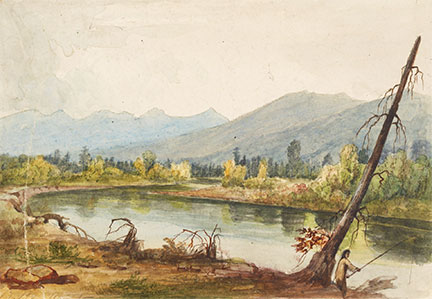

Salish Man Fishing the Bitterroot River Near Present Day Stevensville, John Mix Stanley, 1853

Yale University Art Gallery | Credit: Yale University Art Gallery

non-Indian settlers moved in anyway, particularly after completion of the Mullan Road and the gold rush of 1864. Farms, gardens, and grazing paddocks sprang up in the fine agricultural lands of the Bitterroot to supply the military parties and mining camps. Montana officials rejected the suggestions of some U.S. Indian agents that troops be used to evict or keep out the squatters. Chief Victor had repeatedly pledged to never wage war against the whites, and some of the non-Indians of the area had good relations with the Salish. But many new-comers began to issue demands for the permanent removal of the native people. They wanted their lands, of course, and many also did not believe that traditional tribal ways of life — including the use of fire — had a place in the Montana of the future.

And the Bitterroot was indeed a classic fire-shaped landscape. Many of the Salish place-names in the valley refer to prairies that have long since been logged of their old-growth timber and overgrown with small trees and brush. Countless early non-Indian visitors, from Lewis and Clark on, gave vivid descriptions of those now-vanished ecosystems — the open prairies, the widely spaced ancient ponderosa pines, and even fires or recently burned areas — all of them the record of the long established native practice of frequent, low-intensity fire. All of that began to change, not with the fire suppression efforts after the 1910 fires, but decades before — with the gradual constriction of the Salish way of life in the Bitterroot, and the eventual outright removal of Salish people.

Chief Charlo, 1884

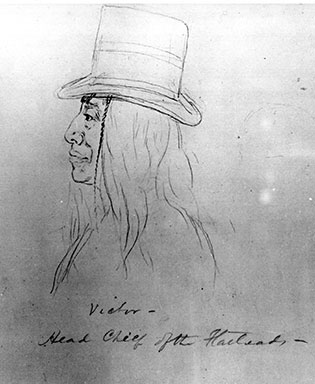

X͏ʷeɫx̣ƛ̓cín (Many Horses or Chief Victor by Gustavus Sohon

Chief Charlo immediately had to contend with President Ulysses S. Grant’s Executive Order, issued in 1871 in response to pressure from territorial citizens and officials, which falsely stated that that the required survey had been carried out, that the Bitterroot had been determined “not to be better adapted to the wants of the Flathead Tribe.” The Salish were therefore to be “removed” to the Jocko or Flathead Reservation.

In June 1872, the US appointed future President James A. Garfield, the Republican party leader in Congress and a former Civil War general, to proceed to Montana and negotiate the terms of the Salish removal. Like his father, Charlo adhered to a policy of non-violent resistance. He asserted both friendship with non-Indians and insistence on Salish rights — including the right to remain in the Bitterroot. Charlo ignored the Garfield delegation’s demands, and even threats of bloodshed, and refused to sign the pre-drafted “agreement” to leave. U.S. officials then simply forged Charlo’s “x” mark onto the official copy of the agreement that was sent to the Senate for ratification. The Salish still refused to be moved, and most tribal people remained in the Bitterroot with Charlo.

In the wake of the "Garfield Agreement," the Government required the remaining Bitterroot Salish to take individual allotments of land, and seized the rest of the Salish lands for white settlement. Even the Salish allotments were then encroached upon or altogether taken by a new influx of non-Indian settlers. Some officials of Missoula County, which claimed jurisdiction over the Bitterroot Valley, attempted to tax the newly defined Salish land and property.

According to the Missoulian, in 1876 Charlo responded to this attempted taxation by saying, “the white man wants us to pay him....for the things we have from our god and our forefathers; for things he never owned and never gave us…He has filled graves with our bones…his course is destruction; he spoils what the spirit who gave us this country made beautiful and clean…To take and to lie should be burned on his forehead…We owe him nothing. He owes us more than he will pay…I have more to say, my people, but this much I have said…His laws never gave us a blade of grass nor a tree nor a duck nor a grouse nor a trout…You know that he comes as long as he lives, and takes more and more, and dirties what he leaves.”

Despite his deep and growing resentment, Charlo stuck to his policy of non-violent resistance. Some settlers nevertheless feared the Salish, and they appealed to the Government for military protection. In1877 Fort Missoula was established in the middle of what whites called the “Hell Gate Ronde” — a classic fire-shaped prairie of over 50 square miles around the confluence of the Bitterroot and Clark Fork rivers. There would be no traditional burnings there anymore. This was the context of tension and conflict that forced the Salish to live in a newly restricted way, including in regard to their use of fire.

Trapper Peak in the Bitterroot Range, 2005

After the Nez Perce war, pressures for removal of the Salish only increased, but Chief Charlo and most of the tribe stayed in the Bitterroot anyway. The chief told Senator G.G. Vest, “You want to place your foot upon our neck, and grind our face in the dust, but I will not go.” The Salish now supplemented their traditional food supply with some limited agriculture, but they continued to live largely by the old ways, including trips east of the mountains to hunt the dwindling herds of bison.

They also continued the traditional use of fire, but clearly on a reduced scale. For a community under such tremendous stress, Salish resistance was characterized by a remarkable degree of self-discipline in avoiding conflict with whites. And because fire was regarded negatively by so many non-Indians, the places where burning could still be practiced were narrowing swiftly, particularly after 1883 and the completion of the Northern Pacific railroad. In 1888, the Missoula & Bitter Root Valley Railroad was built, partly through the allotments of the Salish, who were neither asked permission nor offered compensation. Now the development that was occurring along the mainline of the Northern Pacific would extend through the heart of the Salish homeland. Anaconda copper king Marcus Daly established the city of Hamilton in the southern Bitterroot in 1890. The first major logging in the upper part of the valley commenced at the same time. The transformation of the Bitterroot Valley, of both its human communities and its forests, was accelerating.

Salish at Stevensville during forced removals from the Bitterroot Valley, October 1891. Photo courtesy University of Pennsylvania Museum

That same year, incidentally, Montana became a state. And in the wake of massive drought, searing temperatures, and the diminution of native burning over the previous two decades, forest fires raged across the Northern Rockies — by many estimates, exceeding the total acreage even of the 1910 fires. On the Flathead Reservation, Agent Peter Ronan reported: “The outlook for the Indians on this reservation for the coming fall and winter is gloomy and dismal in the extreme. The drought of this summer has been unknown even to the oldest of the Indians. The face of the country is simply parched and the usually luxuriant bunch grass is burned to the roots on prairie and uplands. Nothing green remains save along the banks of the rivers and the line of the irrigation ditch. The hay crop is almost a total failure; the grain and vegetable crop has suffered in the same way, and not a quarter of the usual amount can be harvested this season. To add to this, the forest is on fire all around us, in every direction. The prairies, where any grass grew this season, was fired also. The smoke covers the country, obscuring the sun, and causing business houses in the town of Missoula to be lit up at early in the afternoons. These conditions will necessitate a call upon the Department for a larger supply of flour as bread-stuff will certainly go beyond the reach of the Indians unless assisted.” i

Since they expected to move in the spring of 1890, the tribal farmers planted no crops that year. But Congress failed to appropriate funds for the removal. The same thing happened 1891. According to some non-Indian observers, the tribe's desperation now reached a level of outright starvation, and many people were forced to sell their few household belongings to non-Indians in their struggle to get enough to eat.

Finally, in October 1891, General Henry B. Carrington and a contingent of troops from Fort Missoula arrived to march the Salish north to the reservation. Charlo called his people together and declared that the time had come. They prayed and announced that they would go. Several days later following an all night feast, the Salish assembled at dawn, loaded horses and wagons and started for the Jocko Reservation. The tribe trailed through Stevensville before the silent gaze of the non-Indians. A survivor of the removal, Mary Ann Combs, likened the trip to a funeral march. She remembered all the people crying about having to leave. Other elders noted that the soldiers did not allow people to stop to relieve themselves, and warned them they would be shot if they ran away. Children riding behind their mothers wondered why the grownups were crying. Years later, when Sophie Moiese was an old woman, she would suffer flashbacks, hearing the women weeping as the people rode slowly north toward the Jocko Valley.

Before arriving at the Jocko church, Charlo directed the people to present themselves in their finest ceremonial dress. The people pulled themselves together, and the tribe came into the valley, led by young warriors riding out ahead on their horses, shooting their guns in the air and singing. The women came behind crying. At the church, a large group of tribal people awaited the Salish and welcomed them to the Flathead Reservation.

Belying popular notions that land in the Bitterroot Valley was desperately needed by settlers, it took the U.S. government over 25 years to sell off the 1872 Salish allotments. Officials repeatedly reappraised the lands and lowered the prices in order to try to attract buyers.

Despite the losses incurred in the removal, the Salish rebuilt their lives on the Flathead Reservation, supplementing their continued hunting and gathering with subsistence family farms and ranches — even though the government reneged on many of its promises of help. Most of the homes promised for Salish people were never built. Still other families decided to return to the Bitterroot on their own. The Sapiel family, for example, moved back and remained there well into the twentieth century. And both there and on the Flathead Reservation, even within the narrowed bounds of tribal life at the end of the nineteenth century, the tribes continued to do some burning — although now on a much more limited scale. Felicite Sapiel McDonald, for example, recalls that her great-granduncle still practiced some burning in the Bitterroot Valley.

If we are to fully understand what happened to the traditional tribal fire regimes of western Montana, and thus to the forests themselves, we must also see that fire history is both an environmental and a political history. As native people were systematically uprooted and confined, as their traditional ways of life were increasingly repressed, so their use of fire was also repressed. And with that, the forests were profoundly changed.

_____________

i National Archives, Washington DC, Record Group 75 (Bureau of Indian Affairs), Letters received by Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1881-1907, Letter number 1889-22434 (monthly report for July 1889).

The story of the forced removal of the Salish from the Bitterroot Valley is crucial in understanding why, and how, the creation of choked, fire-vulnerable forests in western Montana really began long before the active fire suppression of the twentieth century.

Victor's Camp, Hell Gate Ronde, John Mix Stanley, 1853

Yale University Art Gallery | Credit: Yale University Art Gallery

But some important shifts began to happen with the discovery of gold in Montana in 1864, and with the ending of the civil war in 1865. Shortly before, the Mullan Road had been built — a rough wagon track running from Fort Walla Walla to Fort Benton. Settlers began to come into Montana — not only to boom towns like Bannock and Virginia City, but also to places like the Bitterroot Valley in order to grow crops and raise livestock to supply the miners. Encroachment on tribal lands increased, and so did the threats and actual violence against those who exercised their off-reservation hunting and fishing rights, let alone those who burned the land in the traditional way. As historian William Farr has noted, in 1869 a grand jury of Montana’s Third Judicial District “met to address Blackfeet depredations and the threat of ‘roving Indians.’ White settlers accused the Pend d'Oreilles of stealing horses, setting prairie fires, and possibly even committing murder while on their way to hunt on the Yellowstone. The grand jury, hoping to call attention to the ‘exposed condition of the people,’ concluded its report with a recommendation to both the military and the Office of Indian Affairs: ‘Their passage throughout settled valleys should be prohibited by the authorities.’ ”i

Tipis at New Perce Pass

And they also continued to use fire — if perhaps in gradually less expansive ways — as an integral part of that way of life, shaping the landscape and nurturing the plants and animals upon which they depended. Some of the evidence for this can be found in the tree rings examined in recent years by forest scientists. In study after study, they have generally found a consistent record of burning throughout the nineteenth century in western Montana.ii

In addition, the federal government’s presence in western Montana was also relatively minimal, including on the Flathead Reservation itself, where the “Jocko Agency” consisted of little more than the agent, a clerk, and a few employees. Through most of the 1860s and 1870s, the government operation did little for the Indian people it was supposed to be serving, but on the other hand, it also exercised little repressive control over them. The agent and his small crew could do little to stop tribal leaders and the warriors alongside them on their way to buffalo — or on their way to light fires.

In the decades following the Hellgate Treaty, the tribes had by no means been marginalized yet, and western Montana was still contested terrain. And it was also still a regularly burned terrain.

__________________

i William Farr, “Going to Buffalo: Indian Hunting Migrations across the Rocky Mountains. Part 2, Civilian Permits, Army Escorts,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 54 (1) (Spring 2004), 26-44.

ii See, for example, S.F. Arno, H.Y. Smith, and M.A. Krebs. Old growth ponderosa pine and western larch stand structures: Influences of pre-1900 fires and fire exclusion (USDA Forest Service Intermountain Research Station, Research Paper INT-495. Ogden, UT: USFS, 1997), S.W. Barrett, S.F. Arno, and J.P. Menakis, Fire Episodes in the Inland Northwest, 1540-1940, Based on Fire History Data (USDA Forest Service Intermountain Research Station, General Technical Report INT-370. Ogden, UT: USFS, 1997), and Stephen F. Arno, The Historical Role of Fire on the Bitterroot National Forest (USDA Forest Service Intermountain Research Station, Research Paper INT-187. Ogden, UT: USFS, December 1976).

In the decades following the Hellgate Treaty, the tribes had by no means been marginalized yet, and western Montana was still contested terrain. And it was also still a regularly burned terrain. but enormous change was on the horizon brought on by the gold rush, the Mullan Road, boom towns like Bannock and Virginia City, and non-Indian settlments in places like the Bitterroot Valley.

Victor's Camp, Hell Gate Ronde, John Mix Stanley, 1853

Yale University Art Gallery | Credit: Yale University Art Gallery

But some important shifts began to happen with the discovery of gold in Montana in 1864, and with the ending of the civil war in 1865. Shortly before, the Mullan Road had been built — a rough wagon track running from Fort Walla Walla to Fort Benton. Settlers began to come into Montana — not only to boom towns like Bannock and Virginia City, but also to places like the Bitterroot Valley in order to grow crops and raise livestock to supply the miners. Encroachment on tribal lands increased, and so did the threats and actual violence against those who exercised their off-reservation hunting and fishing rights, let alone those who burned the land in the traditional way. As historian William Farr has noted, in 1869 a grand jury of Montana’s Third Judicial District “met to address Blackfeet depredations and the threat of ‘roving Indians.’ White settlers accused the Pend d'Oreilles of stealing horses, setting prairie fires, and possibly even committing murder while on their way to hunt on the Yellowstone. The grand jury, hoping to call attention to the ‘exposed condition of the people,’ concluded its report with a recommendation to both the military and the Office of Indian Affairs: ‘Their passage throughout settled valleys should be prohibited by the authorities.’ ”i

Tipis at New Perce Pass

And they also continued to use fire — if perhaps in gradually less expansive ways — as an integral part of that way of life, shaping the landscape and nurturing the plants and animals upon which they depended. Some of the evidence for this can be found in the tree rings examined in recent years by forest scientists. In study after study, they have generally found a consistent record of burning throughout the nineteenth century in western Montana.ii

In addition, the federal government’s presence in western Montana was also relatively minimal, including on the Flathead Reservation itself, where the “Jocko Agency” consisted of little more than the agent, a clerk, and a few employees. Through most of the 1860s and 1870s, the government operation did little for the Indian people it was supposed to be serving, but on the other hand, it also exercised little repressive control over them. The agent and his small crew could do little to stop tribal leaders and the warriors alongside them on their way to buffalo — or on their way to light fires.

In the decades following the Hellgate Treaty, the tribes had by no means been marginalized yet, and western Montana was still contested terrain. And it was also still a regularly burned terrain.

__________________

i William Farr, “Going to Buffalo: Indian Hunting Migrations across the Rocky Mountains. Part 2, Civilian Permits, Army Escorts,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 54 (1) (Spring 2004), 26-44.

ii See, for example, S.F. Arno, H.Y. Smith, and M.A. Krebs. Old growth ponderosa pine and western larch stand structures: Influences of pre-1900 fires and fire exclusion (USDA Forest Service Intermountain Research Station, Research Paper INT-495. Ogden, UT: USFS, 1997), S.W. Barrett, S.F. Arno, and J.P. Menakis, Fire Episodes in the Inland Northwest, 1540-1940, Based on Fire History Data (USDA Forest Service Intermountain Research Station, General Technical Report INT-370. Ogden, UT: USFS, 1997), and Stephen F. Arno, The Historical Role of Fire on the Bitterroot National Forest (USDA Forest Service Intermountain Research Station, Research Paper INT-187. Ogden, UT: USFS, December 1976).