History

The History of Fire and the Human Use of Fire in the Northern Rockies

History

The History of Fire and the Human Use of Fire in the Northern Rockies

History

The History of Fire in the Northern Rockies

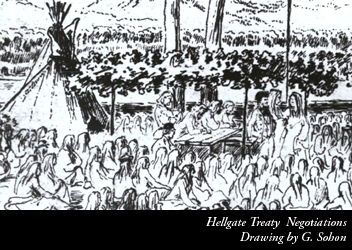

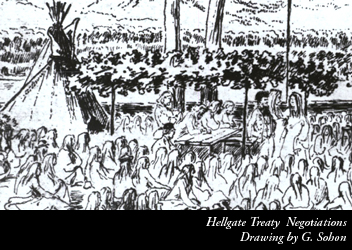

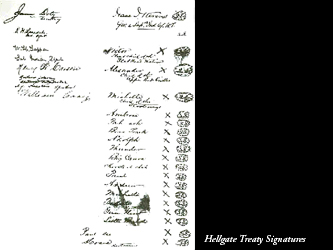

In July 1855, a year after the Jesuits established the St. Ignatius Mission, U.S. government officials convened a treaty council with the chiefs and headmen of the Salish, Upper Pend d'Oreille, and one band of Kootenai. The treaty set the stage for a new political era and greater non-Indian control over what had been tribal resources, including fire.

View the Hellgate Treaty

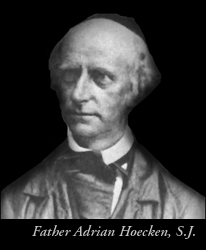

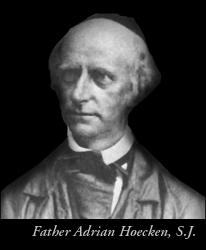

From the start, the Hellgate Treaty negotiations were plagued by serious language barriers. Father Adrian Hoecken, a Jesuit observer, said that the translation was so poor that "not a tenth of it was actually understood by either party."

Stevens’ main objective was to gain for the United States formal ownership of vast tribal lands. As in his treaty negotiations with other tribes in the Northwest, Stevens aimed to concentrate numerous tribes onto a single reservation, thereby clearing the way for non-Indian control and settlement of most areas. But the Pend d’Oreille and Kootenai wished to keep their territories in the Jocko and Mission Valleys and the Flathead Lake area, and Chief Victor insisted that the Salish would never give up their homeland in the Bitterroot Valley. Stevens tried to pressure them, but they refused to change their minds. Throughout the negotiations, the tribal leaders challenged the right of Stevens to demand for such enormous land cessions from these tribes, who had always exhibited exceptional friendship with the Americans. One Salish leader remarked, "If I go in your country and say, 'Give me this,' would you give it to me?.... I have nothing to say about selling the land." And one of the Pend d'Oreille leaders, Nqelʔe (Big Canoe), bluntly told Stevens, "Go back to your country....we never spilt the blood of one of you."

The final treaty language stated that the Pend d’Oreille and Kootenai would stay on the “Jocko Reserve” (the present day Flathead Reservation). The reservation encompasses an area of 1.25 million acres of forested mountains, prairies, and sheltered valleys just west of the Continental Divide, including the Jocko and Mission Valleys, the Little Bitterroot River, Camas Prairie, the southern half of Flathead Lake, and the lower Flathead River from the lake downstream to an area near Plains, Montana.

To the tribal leaders, the treaty language meant that they retained the right to live by their traditional ways, both on and off the reservation. And of course that included the traditional use of fire.

But many non-Indians, disregarding the actual language of the treaty, felt that it meant something else entirely. At first, the treaty had little practical effect. Through the 1850s and early 1860s, the U.S. was a minimal presence in Salish-Pend d’Oreille territory. Tribal people continued to live — and to burn the grasslands and forests — as they had from time immemorial, albeit in a time of declining game populations. But the treaty had nonetheless set the stage for a new political era in Montana. Increasingly, as the nineteenth century wore on, non-Indians would assert greater control over what had been tribal resources. And to many, that also meant asserting greater control over fire.

The final treaty language stated that the Pend d’Oreille and Kootenai would stay on the “Jocko Reserve” (the present day Flathead Reservation). The reservation encompasses an area of 1.25 million acres of forested mountains, prairies, and sheltered valleys just west of the Continental Divide, including the Jocko and Mission Valleys, the Little Bitterroot River, Camas Prairie, the southern half of Flathead Lake, and the lower Flathead River from the lake downstream to an area near Plains, Montana.

Stevens also inserted into the treaty a complicated scenario for the Bitterroot, establishing it as a "Conditional Reservation" for the Salish unless a Presidentially-authorized survey should decide that the "Jocko" was better suited to the needs of the tribe. When the Government did nothing over the next 15 years, the Salish concluded the valley would remain their permanent home. According to the terms of the treaty, the chiefs ceded about 95 percent of their aboriginal territory, and reserved from cession the Jocko-Mission and Bitterroot lands for their "exclusive use and benefit." They also reserved the right to hunt, gather, graze livestock, and fish across all of their old territories.

To the tribal leaders, the treaty language meant that they retained the right to live by their traditional ways, both on and off the reservation. And of course that included the traditional use of fire.

But many non-Indians, disregarding the actual language of the treaty, felt that it meant something else entirely. At first, the treaty had little practical effect. Through the 1850s and early 1860s, the U.S. was a minimal presence in Salish-Pend d’Oreille territory. Tribal people continued to live — and to burn the grasslands and forests — as they had from time immemorial, albeit in a time of declining game populations. But the treaty had nonetheless set the stage for a new political era in Montana. Increasingly, as the nineteenth century wore on, non-Indians would assert greater control over what had been tribal resources. And to many, that also meant asserting greater control over fire.

In July 1855, a year after the Jesuits established the St. Ignatius Mission, U.S. government officials convened a treaty council with the chiefs and headmen of the Salish, Upper Pend d'Oreille, and one band of Kootenai. The treaty set the stage for a new political era and greater non-Indian control over what had been tribal resources, including fire.

View the Hellgate Treaty

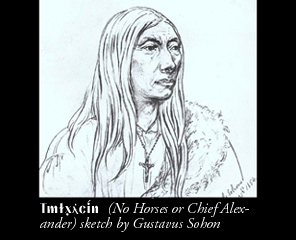

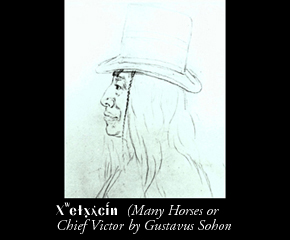

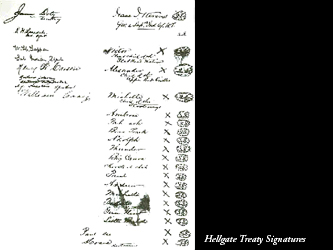

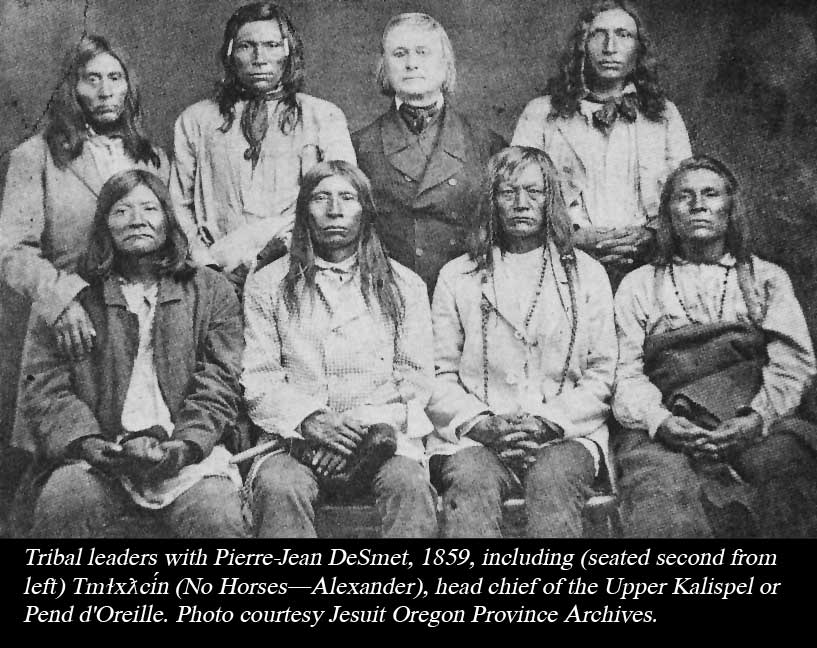

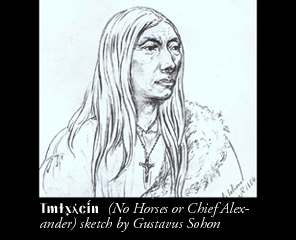

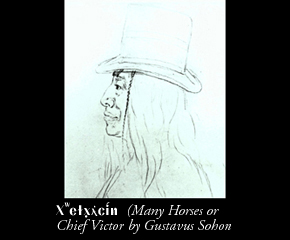

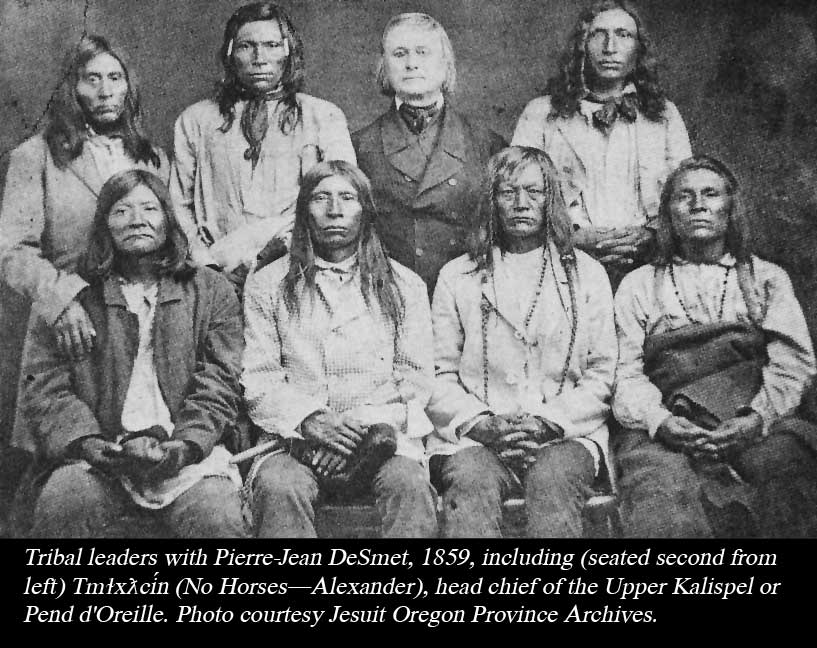

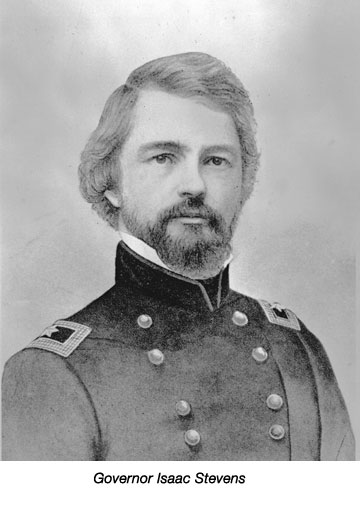

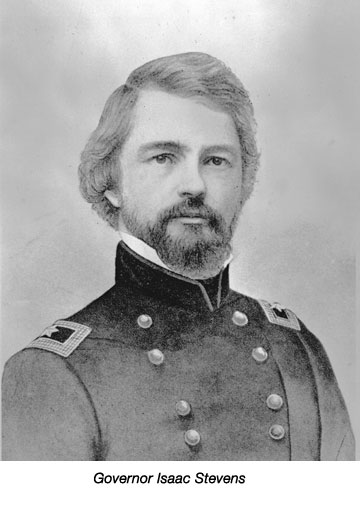

In July 1855, a year after the Jesuits established the St. Ignatius Mission, United States government officials convened a treaty council with the chiefs and headmen of the Salish, Upper Pend d'Oreille, and one band of Kootenai near the present city of Missoula at a place called Čl̓mé, which whites came to call Council Groves. After several days of negotiations, the U.S. officials, led by Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens, and the tribal leaders, led by X͏ʷeɫx̣ƛ̓cín (Many Horses or Chief Victor), signed the Treaty of Hellgate.

From the start, the Hellgate Treaty negotiations were plagued by serious language barriers. Father Adrian Hoecken, a Jesuit observer, said that the translation was so poor that "not a tenth of it was actually understood by either party."

Stevens’ main objective was to gain for the United States formal ownership of vast tribal lands. As in his treaty negotiations with other tribes in the Northwest, Stevens aimed to concentrate numerous tribes onto a single reservation, thereby clearing the way for non-Indian control and settlement of most areas. But the Pend d’Oreille and Kootenai wished to keep their territories in the Jocko and Mission Valleys and the Flathead Lake area, and Chief Victor insisted that the Salish would never give up their homeland in the Bitterroot Valley. Stevens tried to pressure them, but they refused to change their minds. Throughout the negotiations, the tribal leaders challenged the right of Stevens to demand for such enormous land cessions from these tribes, who had always exhibited exceptional friendship with the Americans. One Salish leader remarked, "If I go in your country and say, 'Give me this,' would you give it to me?.... I have nothing to say about selling the land." And one of the Pend d'Oreille leaders, Nqelʔe (Big Canoe), bluntly told Stevens, "Go back to your country....we never spilt the blood of one of you."

The final treaty language stated that the Pend d’Oreille and Kootenai would stay on the “Jocko Reserve” (the present day Flathead Reservation). The reservation encompasses an area of 1.25 million acres of forested mountains, prairies, and sheltered valleys just west of the Continental Divide, including the Jocko and Mission Valleys, the Little Bitterroot River, Camas Prairie, the southern half of Flathead Lake, and the lower Flathead River from the lake downstream to an area near Plains, Montana.

To the tribal leaders, the treaty language meant that they retained the right to live by their traditional ways, both on and off the reservation. And of course that included the traditional use of fire.

But many non-Indians, disregarding the actual language of the treaty, felt that it meant something else entirely. At first, the treaty had little practical effect. Through the 1850s and early 1860s, the U.S. was a minimal presence in Salish-Pend d’Oreille territory. Tribal people continued to live — and to burn the grasslands and forests — as they had from time immemorial, albeit in a time of declining game populations. But the treaty had nonetheless set the stage for a new political era in Montana. Increasingly, as the nineteenth century wore on, non-Indians would assert greater control over what had been tribal resources. And to many, that also meant asserting greater control over fire.

The final treaty language stated that the Pend d’Oreille and Kootenai would stay on the “Jocko Reserve” (the present day Flathead Reservation). The reservation encompasses an area of 1.25 million acres of forested mountains, prairies, and sheltered valleys just west of the Continental Divide, including the Jocko and Mission Valleys, the Little Bitterroot River, Camas Prairie, the southern half of Flathead Lake, and the lower Flathead River from the lake downstream to an area near Plains, Montana.

Stevens also inserted into the treaty a complicated scenario for the Bitterroot, establishing it as a "Conditional Reservation" for the Salish unless a Presidentially-authorized survey should decide that the "Jocko" was better suited to the needs of the tribe. When the Government did nothing over the next 15 years, the Salish concluded the valley would remain their permanent home. According to the terms of the treaty, the chiefs ceded about 95 percent of their aboriginal territory, and reserved from cession the Jocko-Mission and Bitterroot lands for their "exclusive use and benefit." They also reserved the right to hunt, gather, graze livestock, and fish across all of their old territories.

To the tribal leaders, the treaty language meant that they retained the right to live by their traditional ways, both on and off the reservation. And of course that included the traditional use of fire.

But many non-Indians, disregarding the actual language of the treaty, felt that it meant something else entirely. At first, the treaty had little practical effect. Through the 1850s and early 1860s, the U.S. was a minimal presence in Salish-Pend d’Oreille territory. Tribal people continued to live — and to burn the grasslands and forests — as they had from time immemorial, albeit in a time of declining game populations. But the treaty had nonetheless set the stage for a new political era in Montana. Increasingly, as the nineteenth century wore on, non-Indians would assert greater control over what had been tribal resources. And to many, that also meant asserting greater control over fire.